Regardless of your style, this is a good article to share with your classmates and students.

Settling into the hip and relaxing the waist can be challenging as there is usually limited awareness of these regions and they are, at first, difficult to control directly. Trying to maintain balance while moving intentionally can cause one to forget to breathe or to breathe in a shallow way. Unexpected conditions of change can also cause one to hold one’s breath. Breathing naturally and deeply can help greatly since the breath mechanism is physiologically connected to the hip and waist structure.

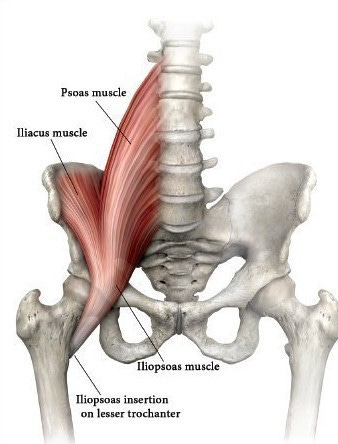

A pair of muscles called the psoas major are anchored in the lower back by several of the vertebrae of the lumbar spine near the point known in Chinese internal arts culture as the ‘life gate’ (mingmen 命門).

The psoas wrap around to the front and are joined deep in the abdominal cavity by the iliacus muscle to form the ‘iliopsoas,’ which descends into the pelvic area and attaches at the lesser trochanter of the femur at the back half of the inner thigh. The iliopsoas joins with other muscles in the region to form a group called the ‘hip flexors’ which act to either draw the upper leg toward the fixed torso or bring the torso toward the fixed leg. The hip flexors also serve to rotate the hip in its ball-in-socket joint. Repeated alternating pulling actions by the iliopsoas pair makes walking possible.

Flexion and release of the iliopsoas can dramatically affect posture and balance since the muscle surrounds the centre of gravity. The psoas can be inhibited in its function when others of the hip flexors dominate flexion, such as occurs during the incorrect ankle twisting movement described herein. Habitual movement of this nature can lead to psoas imbalances, which can be a major factor in several dysfunctions including lower back and hip pain.

In Chinese, the term ‘kua’ (胯) is used to describe the area of the inguinal fold, whose movement coincides with articulation of the hip joint. The kua is identifiable by the visible diagonal folding of the fabric of one’s pants. The fold in an untucked shirt or jacket, descending from the iliac crest down toward the groin area, can also serve to illustrate this.

Sensing the iliopsoas is somewhat difficult, as they lie deep within the body and are not usually experienced distinctly in the way external muscles are. The psoas is unique in the region in that it is the only muscle connecting the spine itself to the legs. At first, developing a conscious relationship with this muscle set must be undertaken indirectly. Later, it is possible to move with a direct awareness of the iliopsoas, for instance, when settling the kua in order to shift through the hip-track. Turning the ribcage while keeping the pelvis and legs fixed—in other words, with no ankle twisting—gently rotates the spine and stretches the psoas from top to bottom. This can help one to identify the top and bottom parts of the muscle. Lifting the leg into a one-legged stance, or to kick, can help one to feel the belly of the muscle.

Deep and conscious breathing can also help one to feel the iliopsoas’ expanse. The psoas provides support for the thoracic diaphragm, a thin dome-shaped layer of skeletal muscle extending across the bottom of the ribcage and connected to the spine by two tendinous structures called crus or, in plural, crura. The diaphragm, which sits directly under the lungs, is the most important muscle used in the breathing process; its function affects blood circulation, metabolism and the internal organs. The diaphragm and psoas are virtually braided together as one of the diaphragm ligaments (medial arcuate) wraps itself around the top of the psoas. The whole structure is encased by connective fascia, providing a web of connectivity that extends to the pelvic floor below and the quadratus lumborum above.

During breathing and other diaphragmatic actions (such as coughing), symmetrical activity takes place between the respiratory diaphragm at the top of the abdominal region and the pelvic diaphragm at the bottom of the abdominal region. Immediately preceding inhalation, electrical activity can be detected in the muscles of the pelvic diaphragm demonstrating the vital relationship between the pelvic floor, the thoracic diaphragm and the iliopsoas. Each of these areas is highly responsive to the status of the others, and when one part becomes even slightly tense, its counterparts are apt to flex in empathetic solidarity. This concurrence can have negative and positive repercussions.

The intimate relationship that exists between the diaphragm, iliopsoas and other parts of the hip and waist has the practical advantage that the proper functioning of any one of the elements can beneficially affect the others. For instance, breathing deeply can relax the iliopsoas and, conversely, release of the iliopsoas can deepen respiration. With every breath the diaphragm and psoas work together to stabilize the anterior spine and, given that the psoas crosses many joints inside the hip and waist, there is also a profound relationship between breathing, stability and movement at the core. One should learn to breath deeply, naturally and consciously as part of the study of the hip and waist.

©Sam Masich