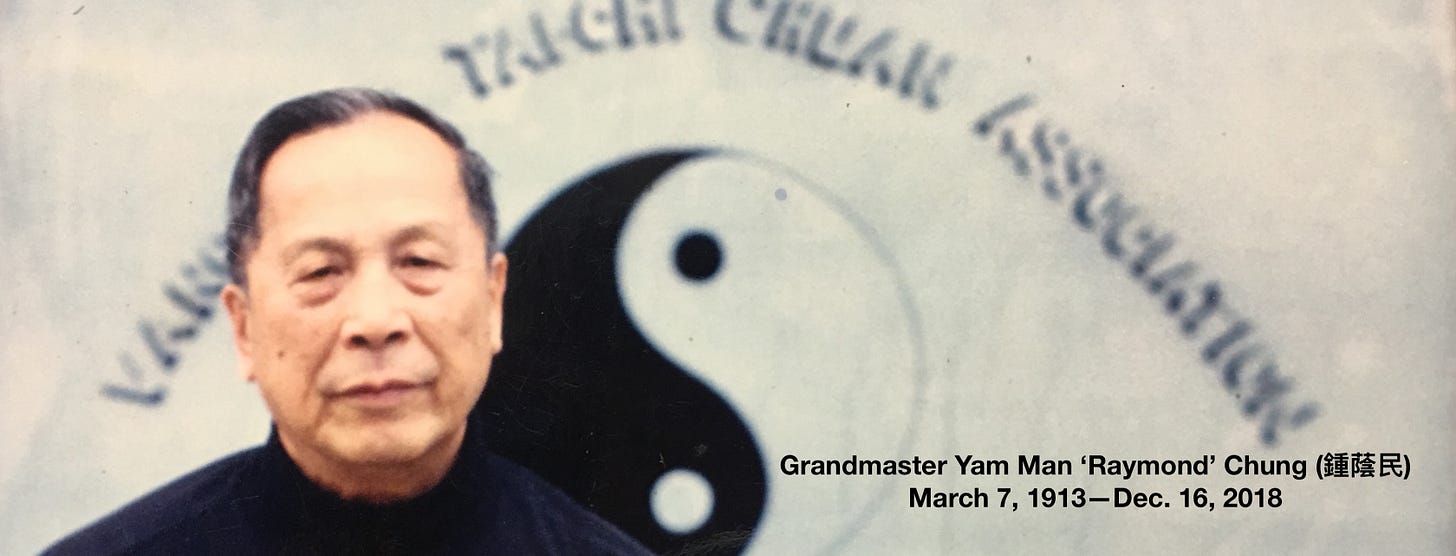

Grandmaster ‘Raymond’ Chung Yam-Man (鍾蔭民 1913-2018) was born March 7, 1913 in Guangzhou (Canton), Guangdong Province, China—just one year after the abdication of the throne by the ‘Last Emperor.’ On January 14, 1962, at age 49, he became one of the first Chinese-born taijiquan masters to emigrate to Canada—it would be seventeen years before he could bring his family to join him. His students called him either ‘Master Chung,’ ‘Sifu,’ or by his anglicized name ‘Raymond’ (‘Yam-Man’ sounds somewhat like ‘Raymond’).

Though he rarely spoke about his past I interviewed him little-by-little from 1985 to the last year of his life. This biography is drawn from those interviews and conversation with his students, especially Brien Gallagher.

Learning taijiquan

During his youth, Yam-Man was active in sports—basketball, volleyball, swimming, and martial arts. In 1933, he began learning taijiquan. His first studies were in the in Canton branch of the ‘Chin Woo Athletic Association’ (Guangzhou Jingwu Tiyuhui 廣州市精武體育會) which offered instruction in various styles of taijiquan and other martial-arts and meditation practices. Most of the classes took place outdoors in parks and gardens. He had many instructors, although, initially, his main Yang-style Taijiquan master was named Ching Chan (程陈; M. Cheng Chen).

Yam-Man trained hard and eventually became an instructor for the association, at first teaching taijiquan for health and exercise, all the while continuing to train the arts of ‘form-will boxing’ (xingyiquan 形意拳), ‘eight-trigram boxing’ (baguazhang 八卦掌), Sun-style Taijiquan (孫氏太极拳), Wu-style Taijiquan (吳氏太極 拳) and the full curriculum of Yang-style Taijiquan (楊氏 太極拳).

Yang Shouzhong

This was a very dynamic period for taijiquan development in Guangzhou since Yang Chengfu (楊澄甫), who had first been invited to teach there in 1932, decided to stay. He spent two years living in the city and teaching members of the social and political elite. Yang Chengfu introduced his eldest son Yang Shouzhong (楊守中) to the Guangzhou martial-arts community and from 1936 to 1949—between the time his father’s death and upon the assumption of power by the Communist government—Yang Shouzhong lived in Guangzhou, teaching taijiquan, often to government officials and military officers, at his father’s behest.

In 1949 Yang left China to begin a life in British Hong Kong (Yingshu Xianggang 英屬香港). For a period of over eight years, during the time Yang Shouzhong was in Guangzhou, Master Chung trained alongside the master. They were contemporaries, roughly the same age (Yang was three years older), and teaching the same style, in the same facility.

Master Chung never claimed to be a close student of the famous Yang master although there exist some taijiquan persons that allege he was. He said they trained together sometimes.

Master Chung was acquainted with a number of well-known taijiquan figures, for example, the famous master and author Dong Yingjie (董英杰), a senior student of Yang Chengfu who had followed the master to Guangzhou in 1932. Dong established himself in the city for many years before moving to Hong Kong in 1949.

Master Chung also knew the famed multi-disciplinary internal martial-arts master Fu Zhensong (傅振嵩), a close friend and colleague of Yang Chengfu, who in 1935 revealed his impeccably researched Fu-style Taijiquan. During the years of the Chung family’s separation, Master Chung’s son Ken Chung (鍾國群) would become a close student of Fu Yonghui (傅永 輝), Fu Zhensong’s son and martial-arts heir. Master Chung’s Vancouver studio wall featured photos of Yang Chengfu and Fu Zhensong side by side.

The war

At age twenty-one, several years before the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War which started in 1937, Chung Yam-Man joined the Guangzhou Air Force Academy (Zhonghua Mingguo Kongjun Guanxiao 中華民國空 軍官校) and received two years of training as a pursuit fighter pilot. In later years, he expressed to students that he loved flying airplanes, especially steep descent, pulling out of the dive, and returning on high.

He fought as a pilot in the war, destroying Japanese bombers, until its conclusion in 1945, eventually achieving the rank of ‘Colonel’ (Shangxiao 上校). He did not like talking about the war and once related soberly that all his friends had been killed in Nanjing during the six-week massacre that began in December of 1937. After the war he spent time in Formosa (Taiwan 臺灣; Republic of China 中華民國) and late,r returned to his home where he worked in the recently founded ‘Guangdong Airlines School.’

Throughout his time in the military, Raymond continued his training of Chinese internal martial arts —but with the perspective of a soldier.

In March 1988, fifty-four years after he first joined the airforce, Colonel Chung and his wife Helen (羅秀擃) saw the unveiling of the ‘Guangdong Province Aviation Monument’ (Guangdong Dongsheng Hangkong Jinianbei 广东省航空纪 念碑) upon which are inscribed the words, ‘Aviation Saved The Nation’ (Hang-kong Jiuguo 航空救國).

The memorial is engraved with the names of 266 pilots that lost their lives in the anti-Japanese war. Master Chung once stated that only he and one other of his two-hundred-plus airforce academy classmates are known to have survived the war. In connection with the aviation memorial, Master Chung and Helen were invited to Guangzhou by the Guangdong Aviators Association (Guangdongsheng Hangkong Jieyihui 广东省航空 眹谊会) to be part of a discourse about aviation history in the region.

After the war

For the ten years prior to the Second Sino-Japanese War, a terrible civil war between the ruling Nationalist Party of China (Zhonghua Guomindang 中 國國民黨) and the contending Communist Party of China (Zhonghua Gongchandang 中国共产党) established great polarity in the country. Animosities continued throughout the war and afterward until finally communist leader Mao Zedong (毛泽东) seized power in 1949, establishing the People’s Republic of China (Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo 中华人 民共和国).

Master Chung clarified, with great insistence, that he’d never engaged militarily with Chinese communist fighters during the war with Japan, although clashes did occur. As an experienced former ‘nationalist’ airforce colonel, Chung Yam-Man had the opportunity to join the Communist Party and become a part of the P.R.C. military—but he refused to serve the new regime. As a consequence, he was sentenced to work in the ‘Reform Through Labour’ (laogai 勞改) program used by the communist government to incarcerate and ‘reform’ those considered to be ‘counter-revolutionary.’

In the period between the end of the war and his incarceration, Master Chung married Loh Sau-Nung (羅秀擃). ‘Helen’ Chung was also a taijiquan expert with a background in Chen and other styles. She too was to be imprisoned as a ‘counter-revolutionary.’ In time, the couple was released for regular conjugal visits—voluntary return was ensured by the threat that other family members could also be censured if either of the pair were not compliant.

Over the following decade, the couple formed a family and, with no end to incarceration in sight, a plan of escape was formed. Chung Yam-Man, while on leave from the laogai labour program, climbed mountains and crossed rivers, eventually meeting up with a farmer who housed and fed him for two days before taking the refugee to Hong Kong on a bicycle. During his time in Hong Kong, he reconnected with Yang Shouzhong who now had a successful studio, and did some training there.

The now forty-nine year old ex-Colonel was able to make his way to Vancouver, Canada as part of an early 1960s Province of British Columbia program that supported the immigration of one-hundred Chinese families from Hong Kong. The program, which acted as a bridge between the harsh anti-Chinese immigration policies of the previous century and immigration normalization in 1967, marked a major shift in the way persons of Chinese origin would be perceived and received in Canada.

In his first year and a half in Vancouver as a new immigrant, Master Chung took some fifteen small jobs, including working in a fish cannery and cooking in a Chinatown restaurant. It was in this Chinese restaurant that other Chinese Canadians realized the cook had other talents.

Vancouver

Once the Chinatown community in Vancouver realized there was a taijiquan master in their midst news spread quickly. Soon, Chinese students began to seek him out for instruction and his notoriety grew. Eventually, members of the Vancouver martial-arts community, including several top level judoka, heard about a Chinese master who could effortlessly throw large men around.

Master Chung’s newly established ‘Vancouver Tai-Chi Chuan Association’ (Yungaohua Taijiquanshe 雲高蕐太極拳社), with its mix of Asian and non-Asian practitioners, was one of the first Chinese martial-arts clubs in North America to break the racial barrier by making the art accessible to anyone who wanted to learn. It was not long before the student demographic would shift dramatically.

During the 1960s, a rapidly expanding counter-culture—exposed to televised images of the Vietnam War and centred in the search for alternative forms of moral authority—became aware of taijiquan en masse. In 1967, a reissued English version of German missionary Richard Wilhelm’s translation of the Chinese classic ‘The Book of Changes,’ or ‘I Ching’ (Yijing 易經), by Princeton University Press, and the release, in the same year, of the first U.S. edition of ‘T’ai-Chi’ by Cheng Man Ch’ing (鄭曼青 M. Zheng Manqing) and Robert W. Smith, brought Chinese philosophy and the art of taijiquan to the top of the youth movement’s reading list.

Soon, everywhere in North America and Europe, young, disaffected ‘hippies’ were seeking out taijiquan instruction wherever it could be found—in Vancouver it could be found with Master Raymond Y. M. Chung.

According to early observers, the first wave of these students, with their long hair, beards and bright clothing, seemed to disorient Master Chung. Suddenly, he was surrounded by a different type of student with a different set of values. By all accounts he took it in stride and welcomed the exuberant personalities of his expanding clientele, however, many from the original group, uncomfortable with the new dynamic, moved on, leaving few original members.

Preparing for the day he would be able to reunite with his family, he prudently invested every extra penny he earned into a ‘small house’ that doubled as his studio. In time, he sold and bought a ‘medium house’ and, a few years later, sold the second house in order to buy a commercial building, a ‘big house’ that offered a large training space with a residence above. In 1980, he was able to bring his family from China after a seventeen-year separation.

Teaching style

Over the decades, Master Chung taught traditional full-curriculum Yang-style Taijiquan to his students, although some aspects, the spear for example, reached only a few students. He enjoyed demonstrating xingyiquan, baguazhang and Sun and Wu-styles of taijiquan to his students on his birthday but he did not teach these art to many students.

During classes, most of Master Chung’s time was spent pushing hands with the students—one after another for hours. His teaching style was not unlike that of many Western fencing masters who stand off to the side of the main class providing mini-private lessons tailored to the needs of each student. A push-hands lesson focused predominantly on defensive techniques with offence being demonstrated gently and rarely explicitly drilled. His teaching method was somewhat abstruse as he gave students their lessons through touch with very little verbalized instruction.

The form class was led by a senior student, usually Master Jack Lee, and together, everyone would practice the various solo and partner barehand and weapons forms. In his younger years, sessions began with Master Chung himself leading the forms practice.

As the main class progressed, each student would be pulled, one by one, from the group in order to receive his or her individualized lesson. For ten-or-so minutes, the pupil was given a push-hand application puzzle to solve. Master Chung would stay on these themes, lesson after lesson, until the learner discovered a way out—the process could take weeks or months. If these problems were not solved, nothing was said on the subject.

If the student did manage to correctly escape one of the applications, there would be a quiet chuckle from the master and then a change of tactics. New puzzle. Students had to figure out the rules of this teaching-game themselves, never having had it explained to them explicitly. The sessions were focused and good natured.

Martial contradictions

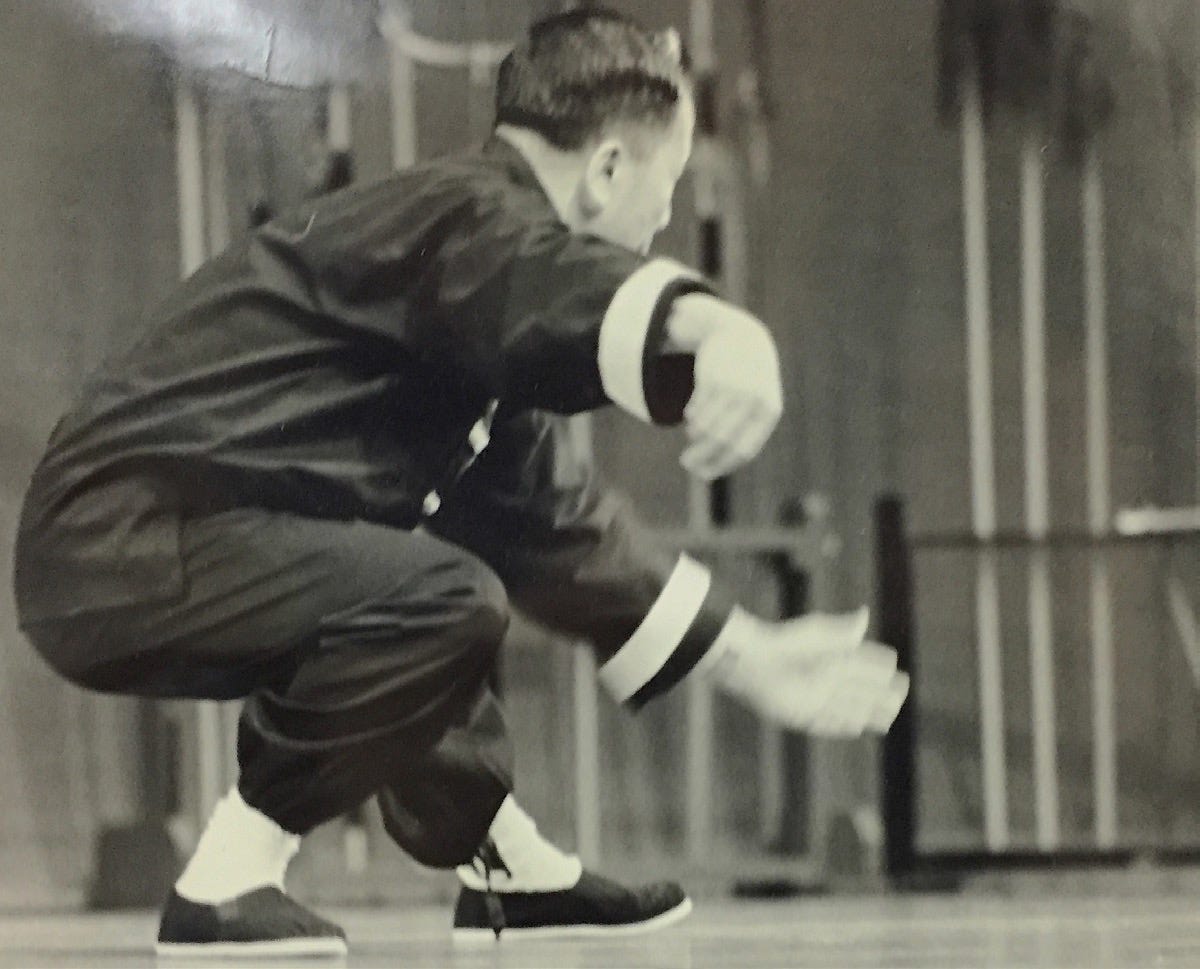

In spite of possessing a highly competitive spirit, Chung Yam-Man seemed to dislike extremes and he abhorred violence in any form. In younger years, Master Chung prepared for his solo-forms training regimen by standing in ‘Horse-stance Post-standing’ (mabu zhanzhuang 馬步站樁) for thirty minutes—while holding a forty-pound stone. Yet he advocated moderation in all things.

Although he had been a steadfast military man, was a serious martial-arts practitioner, and had taught martial applications through countless push-hands circles, he took a dim view of aggressive behaviour in his school. He praised boxing champion Muhammad Ali as the only fighter to use taijiquan principles in the ring but immediately broke up escalating push-hands interactions in the classroom.

Sometime in the early 1970s, he offered Brien Gallagher, his top push-hands student—and a martial artist highly ranked in judo, kendo and, karate—the opportunity to travel together with him to visit all major taijiquan instructors in North America with the intention that Brien should push-hands with—and defeat—all their students, while he would do the same with each master. He intended to finish the tour with a visit to Zheng Manqing’s New York school and show everyone who was who.

In spite of this competitive streak, he didn’t seek after recognition—he never published a book or an instructional video and he seemed to find amusing those taijiquan masters who sought the limelight.

In 1977, a couple of Master Chung’s students thought that it would be hilarious to take their venerable Chinese master to see the newly-released and mind-blowing blockbuster ‘Star Wars.’ At first, the maestro seemed to be enjoying the film but, at some point, when the students looked over, they saw him looking downcast, with his head hung forward, shaking from side to side.

After the movie, one of the students, Bob, asked him if he didn’t enjoy the movie. He looked the young man in the eye and said, “When I young, I not afraid. Now, I afraid.” Combat scenes between imperial TIE fighters and Rebel Alliance X-wing fighters, based closely on film footage from World War II dogfights both inside and outside of the cockpit, were absolutely genuine to his experience. Violence for him was very real thing and not something he wanted in his life.

Master Chung continued to attend to his students until his passing at age one-hundred-and-five.

An audio excerpt from lunch with Master Chung the year before his passing.

Thank you Sam

You do Grand Master Raymond Chung a great service in Protecting his Legacy

You’re dedication to His

Art snd his Memory is Admirable.!

Look forward to more insight on The Father of The Vancouver Tai Chi School