Spirit in Taijiquan and Qigong 神

Sam's comments from an instructor's panel discussion at Tai Chi Caledonia in 2009

Listen to parts of this interview with this archival audio.

Spirit in Taijiquan and Qigong

‘Spirit’ is a quality that is often referred to in the work of taijiquan and qigong and it is also one of the qualities that is considered when evaluating a taijiquan performance in competition. That being said, for many people, ‘spirit’ is a concept that is difficult to explain or put into words. In 2009, at the annually-held ‘Tai Chi Caledonia’ gathering held in Stirling, Scotland, the host, Ronnie Robinson invited a few of the event’s instructors to give their views on the matter. They were Marianne Plouvier (France), Sam Masich (Canada), Faye Li Yip (UK), and Judith van Drooge, (Netherlands). Here, the questions and comments addressed to Sam Masich are featured.

Ronnie: Perhaps a good place to start is (with each of) you saying a few words about what ‘spirit’ means to you.

Sam: Three things come to mind in terms of ‘spirit’ with regards to taiji. One is the standard qigong formula which we see in all qigong and taiji practices – the idea of jing (精) or ‘essential raw energy’ which produces qi (氣) or ‘vital energy’ which animates something and this qi nourishes the shen (神). This is usually translated as ‘spirit.’ So that’s the jing-qi-shen formula; Jing produces qi, and qi nourishes shen.

Another thought that comes to mind when I think about spirit and taiji is a treatise by Yang Cheng-Fu (楊澄甫), which he narrated something that was passed down to us in writing (by Zhang Hongkui 张鸿逵), where he said—I think a very critical thing for taiji practitioners, “It’s important to focus on the shen, not on the qi.” This is a very strong admonishment in his teaching and it comes up with other teachers as well. What I think is interesting about this whole subject is that taiji connects to some very ancient practises, and that the idea of shen is actually ‘spirits.’ So these are the three things that come to my mind when I’m considering the idea of shen or spirit.

Sam: What struck me is that when Marianne was grasping for an approach to this, she didn’t have any problem expressing it in her movement. It was very apparent when she was doing her form and she was absolutely there, in the moment, everything was focused. It wasn’t just about going through the motions she was totally centred and aligned. I was quite captivated by her form and I think it’s very much like what Faye just said, it’s like ‘she’s in the zone.’ That’s interesting. What would it be like to be inside of that place and experience? Whether that was a difficult thing to discuss for some people, it’s possible just to be in it.

Audience member: Do you think it’s something that is intrinsically there or is it something that taiji helps to bring out of you?

Sam: This subject could be a very long discussion indeed. We could ask the questions, “Is it something we can develop?” “Is it something we possess?” Even, “Is it something we’re possessed by?” With most ancient rituals—and China has a deep culture of ritual—it wasn’t really dominated by the big three; Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism. For most of the people's daily lives, for many, many years it was spirits, mediums, trance channelling, exorcism etc. It was about dealing with the spirits that possessed you. Why did you get sick? Bad spirits possessed you. Why did the crops fail? Bad spirits were acting.

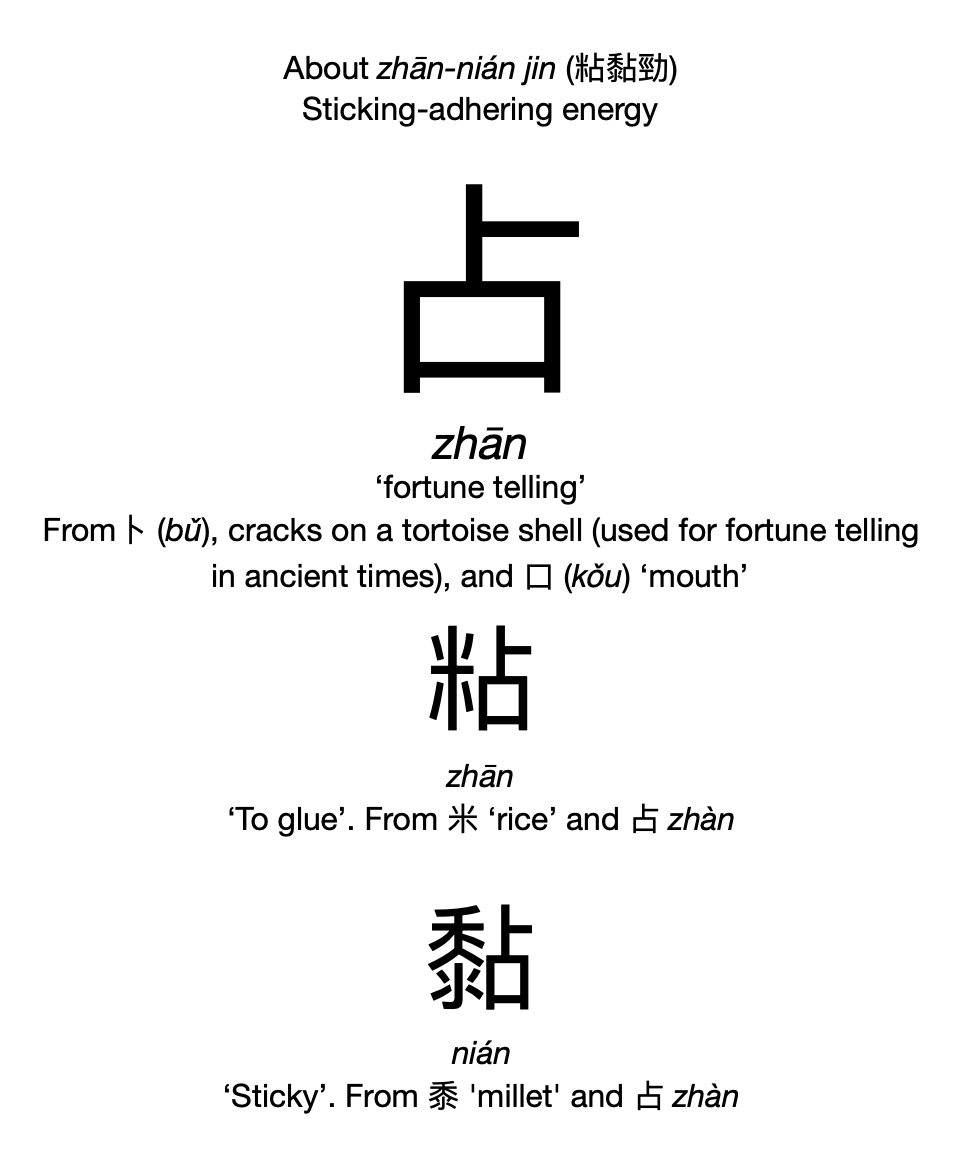

There’s another aspect to this which has to do with giving one’s self over to being occupied by a spirit. Now, personally I don’t believe in any of this stuff, but this experience is a very necessary and primal one for human beings. The fact of giving oneself over to being occupied is important. I think this is what we really see when someone has shen, or is really ‘in the moment.’ In that space they have really opened themselves up to whatever it is that is at the very centre of the art. This is very, very core to taijiquan practice. Concepts like ‘sticking’ (zhan 粘)involve (Chinese) characters that have to do with divination (zhan 占). There is a certain amount of giving over that we need to do, we need to allow things to happen. That requires, as Faye says, ‘real control of your body, your mind, focus, attention, awareness etc.’

Ronnie: So do you subscribe to the notion that there is a shamanic component to this work?

Sam: That’s what I’m saying. For most of Chinese history, for average people, it’s not really dominated by Buddhism priests or Taoist priests or Confucian ethics—that was really for the upper society for the most part. For most of history, people’s lives were influenced by these very basic shamanic elements, and by that I mean four to five-thousand years. So, taiji is actually born in this soil and I think it’s a very deep part of the art which is largely unspoken about.

Audience member: Faye mentioned, and Sam elucidated on, the idea of the requirement for good basic structure having to be in place before shen could happen, do you think it’s possible to have very good technical form without really being aware of the proper application of what they’re doing?

Sam: If you limit the level of what we call very good.

Audience member: We talked about spirit or shen as something that can be acquired, I’d like to suggest that it is something that can only be gained when we let—go of things. You talked about from jing to qi to shen but we haven’t talked about going on to ‘wu’ and to 'emptiness—towards the dao—and to me, in some way, spirit becomes impersonal whereas shen in some ways is within the framework of what we can reach. Whereas, with spirit I feel in we have to surrender not only the personal shen but also the characteristics of what we consider to be important for the evolution of ‘me’ or the self. In a sense the ultimate spirit is that which we find when we give up everything we associate with being ‘me.’; I think that’s also very much part of the system.

Sam: That’s exactly what I was talking about—that abandoning of self that allows one to be occupied by another way of being that isn’t the personal ego.

Audience member: Maybe what we can say is that taiji is only one of many vehicles for the manifestation of the spirit. We can find in many sports, all branches of culture that there is something special there. For taiji to be special in that regard I think is a fallacy—it’s only one of many ways.

Sam: As I’ve said before, I’m an atheist. I also don’t think it’s important which goblin or ghost or which spirit we refer to. To me, they are all the same thing and we just apply different cultural expressions to what happens in the process of opening. Something happens—and it seems to happen universally in all cultures as this gentleman said—and it’s not unique to taiji. There is something about opening to it, and I think like Ronnie said too, we’re just opening it a little, maybe to get out a couple of nights a week, people are doing something a little more positive than going down to the pub regularly. Just the fact that we’re opening things up is important. I think in taiji we all recognize that there’s something more going on than just moving our thighs and moving our arms. There’s something more with this and I think that’s what people yearn for, opening up to spirit. I don’t think there needs to be a single, specific definition for that. It’s that process that is important.

Audience member: Do you think there’s a danger, chasing this spirit, this ultimate, amazing—whatever it is. There’s seems to be an awful lot of people who have gone slightly wacky from chasing something. What I really like about taiji is just really being in that moment and enjoying it and to me that’s spirit to me.

Sam: There is this expression in Chinese ‘zuo huo ru mo’ (走火入魔) which means ‘to walk into fire and enter the devil.’

Faye: It means to lose control of yourself as if taken over by spirits or entities.

Sam: It’s something that qigong masters warn their students about—to be cautious and not to let things go away from reality.

Faye: Yes, when we’re working with this concept of shen it’s important to keep it in context and stay grounded.

Audience member: The Yijing is based on this connection with the spirit dimension, isn’t it?

Sam: This word that is concerned with the idea of ‘sticking’ in push hands is the same Chinese character that’s used in divining with the Yijing (易經). What you’re doing when you’re doing push hands is hands-on divination, hands-on sensing. The stated purpose in the Taijiquan Classics is that the practising of taijiquan is to acquire shenming (神明)—spiritual illumination. It then sets about describing how to do this, by making proper connection, by pushing hands. So it’s a spiritual practice in the form of a martial art. The Yijing is right in the spirit of this.

Audience member: I’m thinking about the (Taijiquan) Classics where it refers to allowing the ‘spirit to rise to the top of the head’ and, as a student and sometimes as a teacher, I think there is an element where somebody may make an adjustment to you, or you make an adjustment to somebody and you see their eyes light up. It’s kind of like you’ve fiddled about with your car and suddenly you have it all connected.

Sam: I had a student who came to class, quite depressed—he was having a few substance abuse problems and every so often he’d drop off the map, go on a bender and then he’d come back and do some taiji. And I remember so clearly one time, he was pushing hands with one of the other students, and just kind of pulling himself out of this state, and he looked at his push-hands partner and said, “Oh… you’re cheering me up.” It was just as if his energy, his qi, was starting to come up, to bring him to a place where he was starting to re-ignite after this full-on bender.

Audience member: Does that also have something to do with a shared feeling? I’ve noticed there’s a much different feeling to doing your taiji alone to doing it with a group of people. It’s like being here at Caledonia. Many of us feel a certain spirit of being at this meeting and perhaps that was the kind of thing that he was feeling too.

Sam: In the Yang Style writings taijiquan is described as a form of ‘asexual dual cultivation’ and, in relating it to the tantric dual-cultivation practices that have to do with sexuality, we are creating a non-sexual dual cultivation with push hands where two people come together and start mingling and melting with these energies. In a way it’s dealing with a similar matter, but in a non-sexual way. We’re giving over to this interplay or exchange of energies and in taijiquan this is considered to be part of the practice of ‘cultivating spirit.’ That’s partly why I feel that push hands is an extremely important part of the art.

Audience member: Is there a danger that if you’re giving your class a spiritual dimension to their teachings that it’s something that they’re not really there for—they’re there to do taiji.

Sam: It’s a great topic really. I think what you’re asking is, “If you come on too strong or too heavy with it, can it put people off ?” Or, “If people don’t realize that they’re signing up for that, are they going to feel uncomfortable?” Maybe they’ve come from a more technically-based approach and they’ll find it strange. I think traditional practice has an answer for that: Get your legs right, get your stance right, learn your waist from your hip, get the postures correct, line up the body. So instead of hammering it home conceptually, which doesn’t tend to be the way of taiji anyway, it’s more about, “Can you feel the ground?” “Do you know where your spine is?” They have to be ignited on another level and then drawn into more subtle considerations by practicalities.

Audience member: I don’t think the two things are in conflict, because no matter why someone comes to class, the thing that will nourish their spirit will relate to the atmosphere in which it’s being taught. If you create an atmosphere that gives them good teaching, gives them the right positioning in a way that is respectful and encouraging, then they will get that part regardless of what they’re doing. I wouldn’t look to get spiritual guidance from my taiji teacher but my spirit might be nourished if they responded to me in a way which is helpful to my process.

Sam: I think also, that in things that have to do with martial arts, people who are really practising can see that ultimately everything in me can come into alignment—in myself, with gravity, connected with my partner, actually have a listening relationship with them—and then kick their ass! (audience laughs). There’s power in that, there’s power in this letting go and making a connection. I think there is this element of the worldly and the intangible—the desire for the experiencing of opening up to something that gives a connection to some kind of power or force that really makes it all very attractive.

About the interviewer Ronnie Robinson

Ronnie was a pioneer of Taijiquan and Qigong in Europe. He cofounded the ‘Tai Chi Caledonia’ gathering which is now in its 26th year. Ronnie was a taijiquan instructor, journalist, and an active participant in virtually every European taiji exchange meeting in the early 2000s. He made invaluable contributions to the Tai Chi Federation of Europe and the Tai Chi Union of Great Britain including publishing forty-nine issues of the the TCUGB’s ‘Tai Chi Chuan & Oriental Arts Magazine.’

Ronnie Robinson passed away March 11th, 2016 after a short, severe illness at the age of 63.