This piece, ‘The Lower Dantian,’ is Part One of a description of the ‘three-centres’ (san dantian 三丹田) concept found in Chinese internal-arts practices for tens of centuries. It begins by exploring the terms ‘dantian’ and ‘qi‘ and continues on to a detailed look at the ‘lower dantian’ (xia dantian 下丹田) which is integral to the practice of taijiquan (太極拳). Future installments will deal with the ‘upper dantian’ (shang dantian 上丹田), ‘middle dantian’ (zhong dantian 中丹田), and how the dantian system works as an integrated whole.

The Lower Dantian

In his ‘Discourse on the Practice of Taijiquan’ (太極拳之練習談) Yang Chengfu ((楊澄甫; 1883–1936) says:

“…descending means ‘sink the qi to the dantian.’” (xia ze qi chen dantian 下則氣沉丹田)

Quoting the The Taijiquan Treatise (Taijiquan Lun 太極拳論), Yang describes dantian in the context of clarifying the terms ‘internal’ (nei 内), ‘external’ (wai 外), ‘ascend’ (shang 上), and ‘descend’ (xia 下), words he recommends be used as guidelines when practicing the taijiquan long form.

History and meaning of ‘dantian’

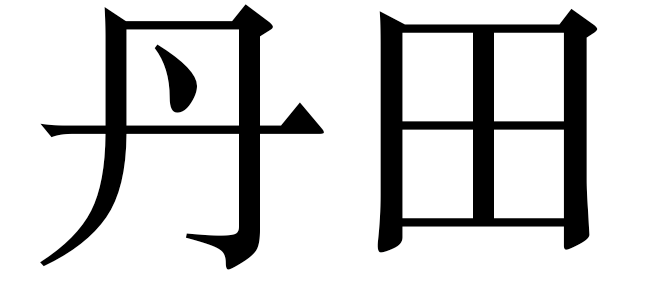

The word ‘dantian’ (丹田) is a metaphoric description of a non-biological region in the body with location but not physicality. The term of ‘dantian’ is in commonly used by taijiquan practitioners and is not typically translated from the Chinese. If it is translated, it is usually just called ‘the centre.’

The term ‘dantian’ (tan-t’ien in Wade-Giles) first appears in the 'Yellow Court Classic' (Huangtingjing 黃庭經), a self-cultivation and meditation manuscript focused on ‘internal alchemy’ (neidan 内丹) that appeared in the Wei Dynasty (魏 220–265; ‘Three Kingdoms’ 三國 period).

Dan

The character dan (丹) emerges from the notion of a ‘well’ or ‘cavity’ with something hidden inside. Like precious ore in a mine, a treasure hidden inside a well, or a coded message, this picture-word suggests a meaning that, if comprehended, provides the key to wisdom and mastery.

Dan is the common term for ‘cinnabar’ (mercury sulphide; HgS), a chemical compound made of mercury (Hg; shuiyin 水银) and sulfur (S; liuhuang 硫磺). Owing to it’s opulent red colour (vermilion) cinnabar has been mined in China for an estimated 4000-5000 years from when it was used to paint walls and floors of important buildings and to adorn stone and, later, lacquer wares.

Aside from decorative functions, the compound had also seen attempts at its use in medicine. However, contact with cinnabar can be seriously toxic and result in nervous system and organ damage as well as respiratory problems if ingested, inhaled, or if coming into contact with skin.

Dan is also translated as ‘elixir,’ or ‘pill,’ in the sense of a small medicinal pellet or ‘wan’ (丸). There is a similarity between the characters dan and wan (compare 丹 and 丸) and many Daoist alchemists consider the ‘mud pill’ (niwan 泥丸) to be the ‘upper dantian.’ In any event, the idea of a pellet or ball inside a larger shape is well expressed visually in the character. Prior to the use of dan as ‘elixir’ or ‘pill’ it was used to mean ‘essence’ (jing 精) and connoted positive traits such as ‘magnanimity’ (dankuan 丹寬) and ‘loyalty’ (dancheng 丹誠). Refinement of ‘essence’ in the ‘furnace’ of the lower dantian is a central aspect of Chinese internal arts practices.

Tian

The character tian (田) means ‘field’ and can be visually understood as a representation of a cultivated farm field apportioned for different crops. Tian is used in several characters and words related to agricultural cultivation: to ‘till land,’ ‘cultivate,’ or ‘hunt’ (tian 畋); an ancient term for ‘pasture’ (dian 甸); ‘turbulent’ (chi 沺)—the image of a flooded field.

A word for ‘farm’ is nongtian (農田), literally ‘peasant field.’ The exact same word can be written nongchang (農場). The word chang (場) is commonly used to mean ‘place’ or ‘field’ in a similar way to tian. For example, ‘airport’ is feijichang (飞机场 S.).

Chang can also mean ‘field in the sense of a region in which particular conditions are present, for example, where a force or influence is in effect. ‘Gravitational field’ (yinlichang (引力场)'; ‘electromagnetic fields’ (diancichang 电磁场); ‘geomagnetic field’ (dicichang 地磁场); 'quantum field theory' is (liangzichanglun 量子场论), and so forth. This sense of ‘field’ is relevant to the definition of dantian since the dantian concept suggests the distinct central location of a particular field or domain.

The dantian is the distinct central location of a particular field or domain.

Location of lower dantian

Several points in the abdominal region have been offered as candidates for the ‘lower dantian.’ Varied systems have understood the dantian to be in diffent locations, for example, in some Traditional Chinese Medicine texts it is suggested the dantian is located one cun (寸, 3.3 centimetres) below the navel on the surface of the abdomen. Others texts have suggested, rather, one cun behind the navel. Some teachers have described the position of the dantian in relation to the intersection between either the ‘governing vessel’ (dumai 督脈), ‘conception vessel’ (renmai 任脈,) or ‘thrusting vessel’ (chongmai 衝脈) with the belt vessel’ (daimai 帶脈).

My master Liang Shou-Yu often compared the ‘real dantian’ (zheng dantian 正丹田) with the ‘false dantian’ (xu dantian 虛丹田). A ‘false’ or ‘seeming’ dantian may be a real and functional point within the system of medicine, meditation, or martial arts but it is not the actual ‘centre.’ For example, the ‘sea of qi’ (qihai 氣海; CV6) is located about five centimetres below the belly button. This point is useful for acupuncturists in the treatment of many disorders and it delivers supports to several forms in taijiquan such as ‘white crane spreads its wings’ (bai he liang 白鶴亮翅). But qihai, often regarded as the lower dantian, is better understood as a ‘seeming’ or ‘false’ dantian.

Dantian as centre of gravity, mass, and movement

The ‘centre of gravity’ or ‘centre of mass’ is a non-visible and singular point residing in the waist region approximately in front of the second sacral vertebra and is where the combined mass of the body appears to be concentrated. The body is maximally stable when the centre of gravity is aligned directly above the centre of the stance, in other words, the line of gravity must reside above the base of support. A lower centre of gravity and a wider base of support—within the structural limits of the joints and muscles of the leg—results in a more stable stance structure. This centre of gravity is correlated with the point known in Chinese medicine and internal arts as the ‘lower dantian’ (xia dantian 下丹田), hence the advice, ‘sink qi to the dantian’ (qi chen dantian 氣沉丹田), found in The Taijiquan Treatise (Taijiquan Lun 太極拳論). Movement of peripheral body parts, the arms, and legs, takes place around, and in reference to, the dantian which can therefore be referred to as the ‘centre of movement.’ The dantian is considered by taijiquan masters to be the specific point from which ‘movement from the centre’ originates.

(excerpt from Foundations of Traditional Taijiquan: Core Concepts and Full Curriculum)

Origin in lower dantian

The location of the lower dantian coincides with the origin of the physical body. It is the place where the process of creation begins after fertilization and where the first cells appear. Thinking playfully, fertilization can be depicted by the character '丹.

Within the lower dantian field a growing mass of cells differentiates to form the embryo with an umbilical connection to the placenta. At this stage, the embryo has formed a top-to-bottom and side-to-side axis—yet no separate body parts are identifiable. This early stage of development is not unlike the character 田.

It is from this ‘centre’ that the body gradually develops, growing to both its inner and outer peripheries. The dantian can, therefore, be understood as an intangible-point-of-origin deep within the belly existing as a remnant of the origin of one’s physical existence.

Functions of dantian

Traditionally, lower dantian practices imagine a furnace-like crucible inside the abdominal region where the production of an ‘elixir of life’ can be enhanced. By synthesizing energetic raw materials—especially misappropriated ‘vital energy’ (qi 氣) and misdirected ‘essence’ (jing 精)—the taijiquan or neigong (内功) practitioner can ‘smelt’ and ‘repurpose’ these crucial forces in service of ‘self-cultivation’ and ‘spiritual illumination.’

The dantian-furnace smelting idea also accords well with the biochemistry of the digestive tract. Carbohydrates, fats, and other food components are transformed into necessary sugars and fatty acids and transported throughout the body by energy-bearing adenosine-triphosphate molecules. Waist-area movement of taijiquan practices massages the internal organs ‘stirring the fire’ in the central furnace helping to optimize the energy-generating process.

Qi

The Chinese character qi is part of many daily-use words such as ‘weather,’ (tianqi 天氣), ‘air,’ (kongqi 空氣), and ‘temperament’ (piqi 脾氣). In qigong, neigong, martial-arts and Chinese medicine ‘qi’ (氣) refers to the ‘vital energy’ or ‘pneuma’ present in all living organisms whose life processes operate based on innate bio-electromagnetic energy. In some branches of Chinese metaphysics qi is be understood as the the basic substrate that comprises the fundamental fields of existence.

The ancient form of the character qi 氣 can be understood as ‘the steam that comes off of rice when it is cooked.’ Therefore, it can be thought of as somewhat ‘vaporous’ or ‘misty.’ In its natural state steam can permeate some barriers but tends to condense onto surfaces. If qi is to gain focused potency it must be directed by natural or contrived processes, for example, in the way steam drives turbines to produce electricity or propel large ships.

In internal-arts disciplines the lower dantian is understood as the place where qi originates and, consequently, from-where qi is emitted, to-where qi returns, where qi can be stored, and where qi can transformed.

Due to its facilitating so many diverse functions—qi production, qi processing, qi utilization, qi movement—xia dantian has acquired many colourful names: the ‘crescent moon furnace’ (yanyue lu 偃月爐)—the image of a crescent moon laying on its back cradling a furnace used for ‘smelting’ energies. It has also been called: ‘the true tiger,’ ‘the infant's place,’ ‘the mulberry palace,’ ‘the water crystal palace,’ ‘the gate of the feminine,’ ‘the gate of origin,’ ‘the stone gate,’ ‘the place of true unity,’ ‘gold within water,’ ‘the tiger facing life within water,’ ‘the one yang returning to origin,’ ‘the moon at the bottom of the sea,’ ‘the human light,’ ‘the foundation of primordial self,’ and more.

In Japanese the words ‘hara’ and ‘tanden’ (たんでん/丹田) are used interchangeably. Hara, which figures greatly in the study of Japanese martial-arts and self-cultivation disciplines, uses the kanji (Chinese) character fu (腹). This character contains, as a main component, ‘fu’ (復) which is the twenty-fourth hexagram (䷗) of the ‘Change Classic’ (Yijing 易經) and means ‘return’—a fitting image for the place that must always be returned to.

The lower dantian is the place where the ‘elixir’ coalesces. Since this is similar to a seed sown in a pasture which naturally gives birth to sprouts and fruits that ripen in due time—it is described as a ‘field.’ Generally speaking, daoism and medicine agree on one important point with regard to the position of the lower dantian—this is the point that directs the functioning of the entire body. (Wang Mu, Foundations of Internal Alchemy)

Dantian in taijiquan

The Taijiquan Treatise states:

Gradually, as one’s touch matures (zhao shu 著熟), ‘comprehending energy’ (dong jin 懂勁) is awakened. As a result of ‘comprehending energy’ (dong jing 懂勁) one progresses toward ‘spiritual illumination’ (shen ming 神明). Reminding the reader that this involves ‘long, persistent, and arduous practice,’ the Treatise councils:

‘Empty the neck to lead essence to the head-top’ (xu ling ding jin 虛領頂勁) and; ‘Sink vital qi to the dantian’ (qi chen dantian 氣沉丹田).

Learning to centre oneself around the dantian is important for the martial artist in order that movement be intentional, powerful, and connected. Equally important is knowing how to disrupt the internal equilibrium of the opponent. Learning how to ‘listen’ (听) and ‘comprehend’ (懂) through touch can enable direct dantian-to-dantian influence of the opponent. Maintaining inner stability while making the other unstable creates a great advantage in self defence. Carpe Dantian!

Organizing one’s structure around the dantian provides a basis for studying taijiquan at advanced levels. It is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve the settled quality that allows both the receiving and expression of force if ‘domain qualities’ are not harmonized with their regional dantian. For example, if the body’s parts are not coordinated so as to allow the lower dantian to remain at the centre-of-gravity position, the structure will become physically untenable and little force can be received or expressed.

Fear of falling

The fear of falling is an inborn emotion based in dread. In the wilderness falling can lead to injury or death—or even worse. The inability to rise from a fall could lead to being devoured by any number of predators. A loss of physical equilibrium triggers co-contractive responses to preserve uprightness and one urgently seeks something to grab on to. Many ‘obstructive behaviours’ that lead to ‘errors’ in taijiquan are rooted in the fear of falling. The practice of sinking qi to the dantian is an alternative to such obstructive behaviours and, therefore, stands as one of the most important concepts in taijiquan as a prerequisite for success in the art.

Dantian fun!

Yang Banhou, the eldest son of taijiquan master Yang Luchan, was reputed to lay grains of rice on his abdomen, then shout, 'Ha!' The rice pellets would be launched and stuck into the ceiling. This was to test his inner power.

On a few occasions I stood alonside my teacher Master Jou Tsung Hwa as he lay on his back, launching a coin into the air using abdominal power—I would catch the coin at the height of my own lower dantian.

Master Jou believed intensely the cultivation of qi through the strengthening of the dantian and in the pursuit of spiritual enlightenment through practice of taijiquan. He thought that all serious taijiquan players should be able to launch a coin at least one foot into the air with their belly.

Life-nourishing waist

Attention to the waist region is an important part of internal self-cultivation practices belonging to the health philosophy called ‘nourishing life’ (yangsheng 養生). Lack of abdominal activity can have serious health consequences. By focusing on xia dantian taijiquan players can continually deepen their understanding of the waist region and its qi-management.

Best article I've read in a while! Thanks Sam.

Good one Sam! I enjoyed it, thanks.

Keep head low and eyes high!

P