Variations of the ‘twenty-question interview’ have appeared in print and online in several martial-arts publications over the years. This version has been updated for my Substack readers.

Twenty Questions: An Interview with Sam Masich

1. What led you to take up taijiquan?

In 1979, when I was seventeen I left my hometown in north-western Canada and moved to Vancouver. I was passionate about drawing, oriental philosophy, and sports —especially soccer. When I first discovered martial arts I saw right away the chance to fuse the essence of all these interests into one activity.

2. You started out training in Yang-style taijiquan (楊式太極拳) and in judo (柔道). Did you study both of these arts from Brien Gallagher and did you train in these arts simultaneously?

I began with judo with Brien Gallagher but it was his taijiquan that I really wanted. I more or less tricked him into teaching me taijiquan. Once we got going with the taiji however, we trained both arts together. I actually learned the Yang long form in a judo gi after judo sessions.

I trained three times a week at one club and three times a week at another—all with Brien. After the Tuesday, Thursday and Sunday trainings we’d do taijiquan. At some point we switched our Sunday training to only taiji at his home dojo. I trained with him from 10am to 5pm, one-on-one for more than five years of Sundays of the seven years I apprenticed with him. We never missed a Sunday session except for Christmas.

3. Can you tell us something about your first teacher, Brien Gallagher, and what it was you trained with him?

Brien was an ex-police officer and champion pistol shooter. Even now, in his seventies he is a champion archer. He’s been a national level judo and kendo competitor and won provincial championships in these and in karate sparring. He can ‘read’ people in push-hands with a few light turns of the circle. He has the sharpest eye and the fastest, yet softest, hand of any martial artist I’ve thus far met. He’s also proudly Irish and comes from a long line of bare-knuckle fighters. He first learned boxing from the priests who taught at his school. His family actually has its own headlock, which has been passed down secretly through generations. He is a superlative martial-arts trainer having coached all of his seven nephews to provincial championships in judo.

In taijiquan he is one of only two practitioners certified as Master ‘high-level’ by his teacher Grandmaster Raymond Y. M. Chung (鍾蔭民). Master Chung had been in the same academy and trained alongside Yang Shouzhong (楊守中) (Yang Chengfu’s eldest son). He is a master of the full curriculum of Yang-style Taijiquan as well as being a high-level baguazhang, xingyiquan and Wu-style Taijiquan practitioner.

4. You worked closely with Dr. Yang Jwing-Ming (楊俊敏), how did that come about and what you learn from him?

Brien and I would refer to Yang Jwing-Ming’s first book, ‘Yang Style Tai Chi Chuan’, as it followed a curriculum very similar to the one Brien had learned from Master Chung and was passing on to me. I felt a very strong connection to Master Yang and his teachings even before meeting him some years later.

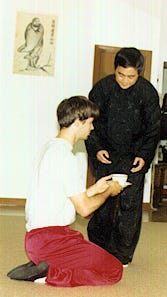

While I am a tudi (徒弟) (formal disciple) of Master Yang, I never learned his complete system. He taught me deeper, principle-based material as he knew I was already sitting atop a very solid curriculum. Rather than messing with it, he had the foresight to help me fill in the gaps in my understanding and the means take me deeper and further in the direction I was already going with Brien and Master Chung. We focused on qinna (擒拿), straightsword, and bare-hand applications, push-hands, and neigong (內功). He helped me to better understand the Chinese characteristics of Chinese martial arts—the history, philosophy and the cultural meaning and ‘feel’ of what I was doing.

A young hot-shot tournament champion does not automatically possess humility regarding the vast scope of the art. Master Yang helped me to see things in perspective and thus temper the pride I felt in my achievements. He would always say, “The higher the bamboo grows, the lower it bows.” Also, he taught me to respect the classical writings and the symbolic concepts within taijiquan lore and steered me toward the practical pondering that informs my work today. Finally, by his epic example—he is probably the most widely published author in the subject of Chinese martial arts—he has given me a sense that I have a responsibility toward leaving the art in a better state than I found it.

5. How did you come to work with Liang Shou-Yu?

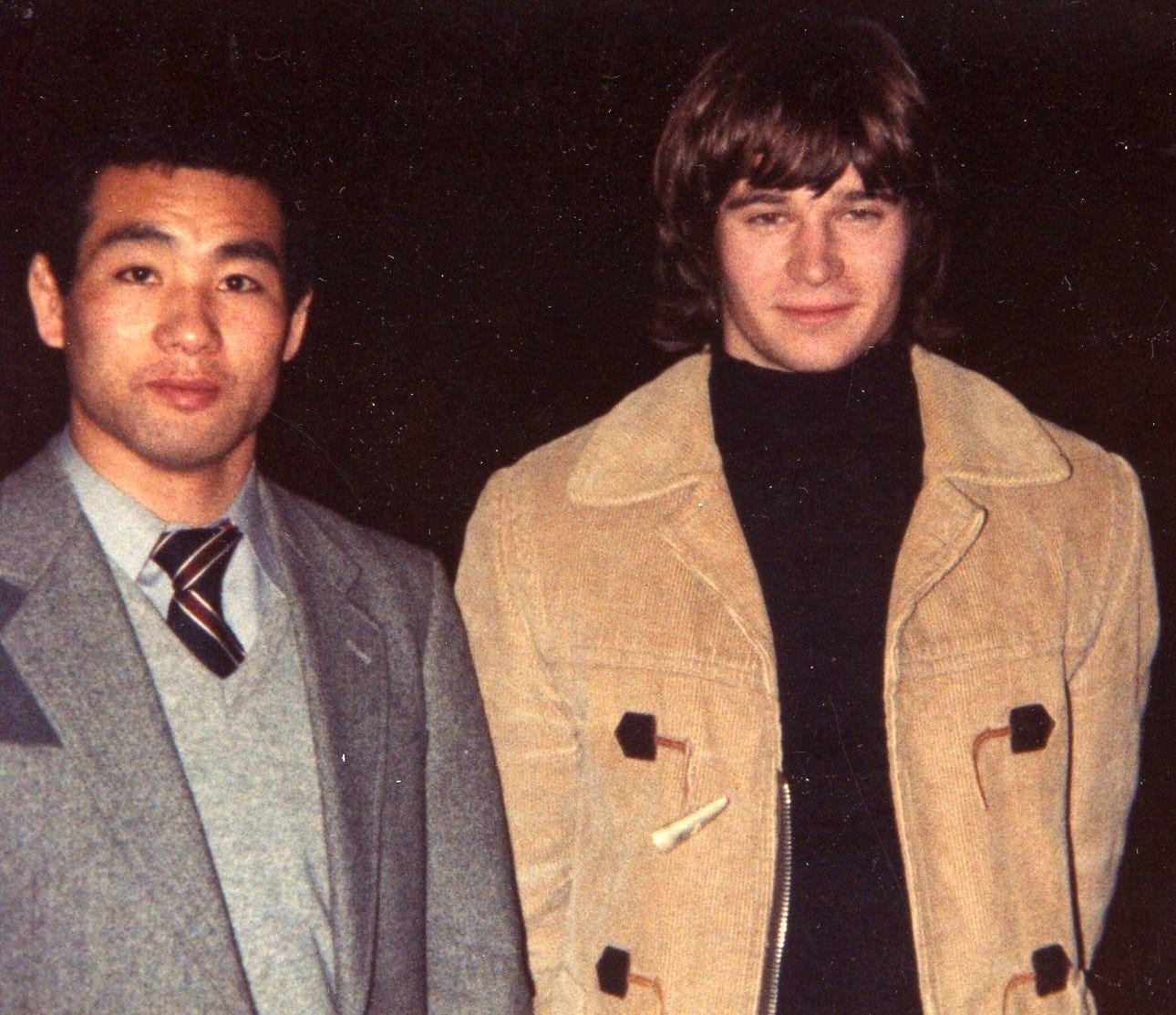

I first met Master Liang Shou-Yu in the spring of 1985 at an event to choose the Canadian national Chinese martial arts team to compete in the first International Wushu Championships in Xi’an, China. I was there with Brien who had managed to get me into the tryout through the recommendation of Master Chung.

Brien and I were sitting watching the various wushu athletes and I was—not having seen modern wushu performed by caucasians my own age—completely impressed. As a former long jump, high jump, and triple jump athlete I thought, “These guys are great—I’d like to do that!” Brien didn’t seem so dazzled with it all. He’d seen it all before. He’d done it all a long time ago—though not necessarily with wushu.

I demonstrated my form (and made the team) and was a bit flustered when I sat down. Then, a forty-ish year old Chinese man stood up to perform. He moved for about ten seconds and Brien leaned over to me and said, “That’s real.” That was the first time I saw Liang Shou-Yu move.

Master Liang and I connected well on the 1985 trip to Xi’an where he was the team coach and I was one of the athletes. He helped me out of a difficult jam at one point and set it up for me to train push-hands in Beijing with master Men Huifeng (門惠豐). When I came back to Canada, Brien prepared me for about a year, enabling me to study Chen-style taijiquan privately with Master Liang who then trained me in a very different way than I’d been used to. Stance structure, alignment, flexibility, and flavour—he taught me the secret passages between styles and opened up new ways of grappling and weapons use. He first taught me Chen-style Taijiquan (陳式太極拳) (both of the traditional routines, push-hands and sword) then later Ermei bafa (峨嵋八法), xingyiquan (形意拳), baguazhang (八卦掌), liuhebafa (六合八法), shuaijou (摔跤), kuaijou (快跤), chojiao (戳腳), and a lot of sword, spear, and other things.

6. What do you mean when you refer to ‘secret passages’ and why were they ‘secret?’

By ‘secret’ I’m referring to knowledge that comes with broad perspective and deep understanding born of experience. Within Chinese martial arts there are certain qualities understood to be common to all styles. For example, ways of stepping and of linking the body internally to generate power—a basic corporeal and energetic language that enables one to ‘get it’ no matter the style. Many taijiquan practitioners, because they are focused entirely on taijiquan lack these sensibilities and consequently spend a lot of time ‘reinventing the wheel.’ They are unable to distinguish between general Chinese martial-arts concepts and those unique to taijiquan. It is therefore easy to misconstrue, exaggerate, and undervalue aspects of the training. The upside to this is a lot of creative innovation in terms of approach and descriptive language. The downside is a tendency to wander away from the root of the art.

7. The curriculum studied under Liang is vast. How did he blend the different methods into a cohesive and progressive martial-arts program?

Master Liang completely defies categorization. He is in every way a genius in the field of Chinese martial arts: physically, martially, intellectually, civilly, spiritually. It's really only when one reaches something of a high level in this work that appreciation of a Liang Shou-Yu can meaningfully begin. Like many individuals of enormous capacity, he has developed his own way of organizing his understanding.

Master’s Liang’s personal system—in many ways an homage to first his martial-arts master, his grandfather— is called Shushan Wuji Xiaoyaopai (蜀山無極逍遥派). Shushan is a regional nickname for Sichuan Province and refers to the mystical martial-arts mountain Ermeishan (峨嵋山). Wuji is the ‘pre-primordial’ to taiji—the state of un-beginning and a reference to the fact that Master Liang is now acknowledged in China as the only living grandmaster of the actual wujiquan (無極拳) system. Xiaoyao means something like ‘footloose’ or ‘care free.’ I think this is a perfect summary of Master Liang: open-minded and free, yet deeply rooted in his native tradition.

It is why he is capable of, as he now does, pulling together tens of thousands of practitioners from entirely disparate disciplines and backgrounds.

You hit the nail on the head when you say cohesive and progressive program. His top students are invariably amazing in their breadth and depth. But Master Liang’s work is not so much about getting any individual student to take in all that he has to offer (I’d guess nearly impossible) as much as in encouraging individuals with widely differing interests coming together in—so to speak—the field of this understanding. He is unique in this regard and perfectly suited to be a global ambassador for the martial arts.

One time I was training baguazhang at his house and trying to master a particularly tricky gesture. I kept making new mistakes in trying to fit myself into the constraints of the form. I’d solved hundreds of these types of problems before, but this eluded me entirely. Master Liang showed it to me again, slipping with easy familiarity into a vortex I hadn’t yet even identified as existing. I made one of those half-in-frustration, half-in-awe comments like, “Gee Master Liang, I’ll never be as good as you.” He stopped and looked me squarely in the eye. “Sam, you think about wrong. Everybody thinking this way. Just you practice this one movement 15 minutes every day—one week, two weeks—you got it. Nobody do this way. Everyone say like you. Why learn if cannot get?”

I know not every student will master every move. But I also know that they can all make satisfying progress and be fulfilled in their practice. This is rewarding to me. It’s very important how I address and encourage them. They have to be made aware that they not only can do taijiquan, they can master it—even if only some parts. I was fortunate with Brien, Master Liang, Master Yang, and Jou Tsung Hwa to have learned with each of them privately, behind closed doors. Although my classes are usually in seminar format, I try to talk to each student as if it were a lesson tailor made for them.

9. Dr. Yang and Liang Shou-Yu seem to have a special bond as martial artists and friends. Was it Dr. Yang who introduced you to Liang? How did you come about meeting and later studying with Liang?

Although I was aware of Yang Jwing-Ming’s books before I’d met Master Liang, we actually met him together in person in Houston, Texas in 1986 when we were all at the same event. They’d already been in correspondence and Master Liang had shown me some of Dr. Yang books and asked me what I thought of him and the books (since he could not yet read English). The meeting was at the first-ever all-Chinese martial-arts event held in the USA, organized by Dr. Yang’s first tudi and my elder martial arts brother Jeff Bolt. I was a competitor and they were judges.

I followed both Masters Yang and Liang around Canada and the U.S. like a shadow for the next ten years. I went to events and competitions if either of them was involved and persistently inserted myself into any learning situation I could. They both took my education seriously and, in mutual consultation, both accepted me a formal disciple.

10. So it seems you had access to a wide range of skills to train. How did the various teachers present the different material to you and which do you feel had the most influence on your work?

With Brien I learned about martial arts in a general sense. Because his background included western, Japanese and Chinese martial arts he easily navigated between the three worlds with ease. I had exposure to judo, karate, kendo, boxing, Yang, Chen, and Fu styles of taijiquan, and police self-defence training before I met my Chinese teachers. Masters Liang, Yang, Jou, and others (Yang Zhenduo, Chen Xiaowang, etc.) helped me to develop my main interest—Yang-style taijiquan.

Depending on which aspect is in the foreground, any of my teachers could be considered the most influential. Master Jou Tsung Hwa impressed on me very deeply the notion that, ultimately ‘taijiquan is the teacher.’ My instructors have been like different lenses, each allowing me to see the art in different ways. My work is not so much about reconciling these differing views but in seeing clearly as I polish and refine my own unique lens.

11. Many new generation of Chinese martial artists are not aware of the contributions and pioneering work done by Jou Tsung Hwa. What can you tell us about your experiences with Jou as a martial artist and as a person?

Master Jou understood better than anyone that taijiquan and the internal arts thrive best in community. He didn’t believe in cliques and secretive teachings. By his very presence he broke down the barriers erected by the self-important and the manipulative in taijiquan society. One might have been tempted, on first impression, to dismiss him as a harmless, kooky eccentric and something of a lightweight as far as martial concerns go. But he is, to date, the only person to have bounced my head-top on a doorsill while pushing-hands. He practiced taijiquan with the fervour of an idealistic young student yet was one of the most renowned figures in mathematics education in Taiwan. In high school and university, Yang Jwing-Ming studied math textbooks written by Jou Tsung Hwa. Master Jou taught me to be as focused as an eagle in my hunt for understanding and mastery but not to take myself too seriously, no matter what accolades or criticisms might come my way.

12. Several other teachers influenced your studies. Since this list is vast, please summarize some of the most pointed and unique aspects of skill you derived from each.

Whew! Okay, other teachers (in order of birthdate):

Master Raymond Yam-Man Chung (鍾蔭民; 1913-2017)

What an old generation master is really like. A ten foot stone, half of it underground, covered in thick, soft moss. Passed at age 105.

Master Jou Tsung Hwa (周宗樺; 1917-1998)

Preserving the ancient rituals. Seeker of immortality through taijiquan.

Master Yang Zhenduo (楊振鐸; 1926-2020)

Holder of the global vision of the Yangs and the art they developed. His great-grandfather proclaimed, “I believe taijiquan can save the nation!”

Master Men Huifeng (門惠豐; 1937-)

How do you keep your shoulders relaxed when you put your fingers in an electrical socket?

Master Brien Gallagher (July 9, 1939-)

Your opponent—notice which foot he trusts. Three turns of the hand, I know everything.

Master Liang Shou-Yu (梁守渝; 1943-)

What is the difference between steel feather and a floating brick?

Master Chen Xiaowang (陳小旺; 1945-)

Qi is not at all mystical but it is absolutely essential.

Dr. Yang Jwing-Ming (楊俊敏; August 11, 1946-)

The only person that has made me feel queasy just watching an application.

Master Yang Jun (楊軍; 1968-)

Poise under pressure. Discipline and excellence. The torch-bearer.

Roger Langrick (acupuncture)

How did I know where it is? Because it’s there.

(Le salle de) Maitre Bac Tau (foil, épée, sabre)

First know the foot, then know the sword. Fingers are faster than wrists.

I’ve learned much from many and continue in my quest for understanding.

13. When did you visit China for the first time and what can you share about this experience?

The first visit was in 1985 for the competition in Xi’an that I mentioned earlier. It was only nine years after Mao’s death so everything was pretty much like it was a decade before—thousands of bicycles, very few private vehicles. Taxi drivers were the richest people because they could get tips, overcharge foreign clients and trade foreign currency on the black market. I actually had to do to get out of a jam. I was 23 years old and my money had stretched all the way. I was supposed to pay my room fees at the Beijing Physical Culture Institute (now called the Beijing Sports University (北京体育大学)) with F.E.C. (foreign exchange currency) but didn’t have enough. I changed my remaining money for renminbi (the Chinese indigenous currency) which foreigners were not technically permitted to have. Local people wanted F.E.C. because they could use it to buy things not otherwise permitted Chinese citizens. Shady characters behind a fence and a small ‘tip’ for the person who arranged it for me. University very unhappy about my paying in local currency—threats of calling the police and so forth.

There were statues of Mao everywhere and people still spoke slogans like. “The sun is red, the sun is great, the sun is our party. We love Chairman Mao. We love our party.” Training foreigners in contact aspects of martial arts had been recently forbidden. A jackass American visitor in 1984 had decided to ‘try’ Chen Xiaowang in push-hands in an awkward impromptu public match. It was an impolite ambush that led to some unproductive scuffling and the ban on teaching foreigners sparring skills. I was, however, fortunate enough to have an introduction card from the head of the sports university’s wushu department Zhang Wenguan (張文廣) to whom I was introduced by Master Liang when we were in Xi’an. With that—and some stubborn persistence—I managed to get past the 24 Movement Simplified Taijiquan instructor to a meeting with Master Men Huifeng (門惠豐), the assistant director of the institute and a top flight push-hands master as well as creator of the standardized 48 Movement Combined Taijiquan.

At first, he explained that he couldn’t teach me due to the ban. In response, I leapt up high, flipped in the air landing on my back on the stone floor. Bouncing up I said (through the interpreter), “See, I won’t get hurt.” He laughed and said, “Tomorrow meet me in such-and such room. You come alone. No translator.” After that he gave me daily for two weeks, three-hour long one-on-one lessons on push-hands and qigong. I didn’t understand a word he said but he reshaped my push-hands enough to set me on a trajectory that to this day defines my work.

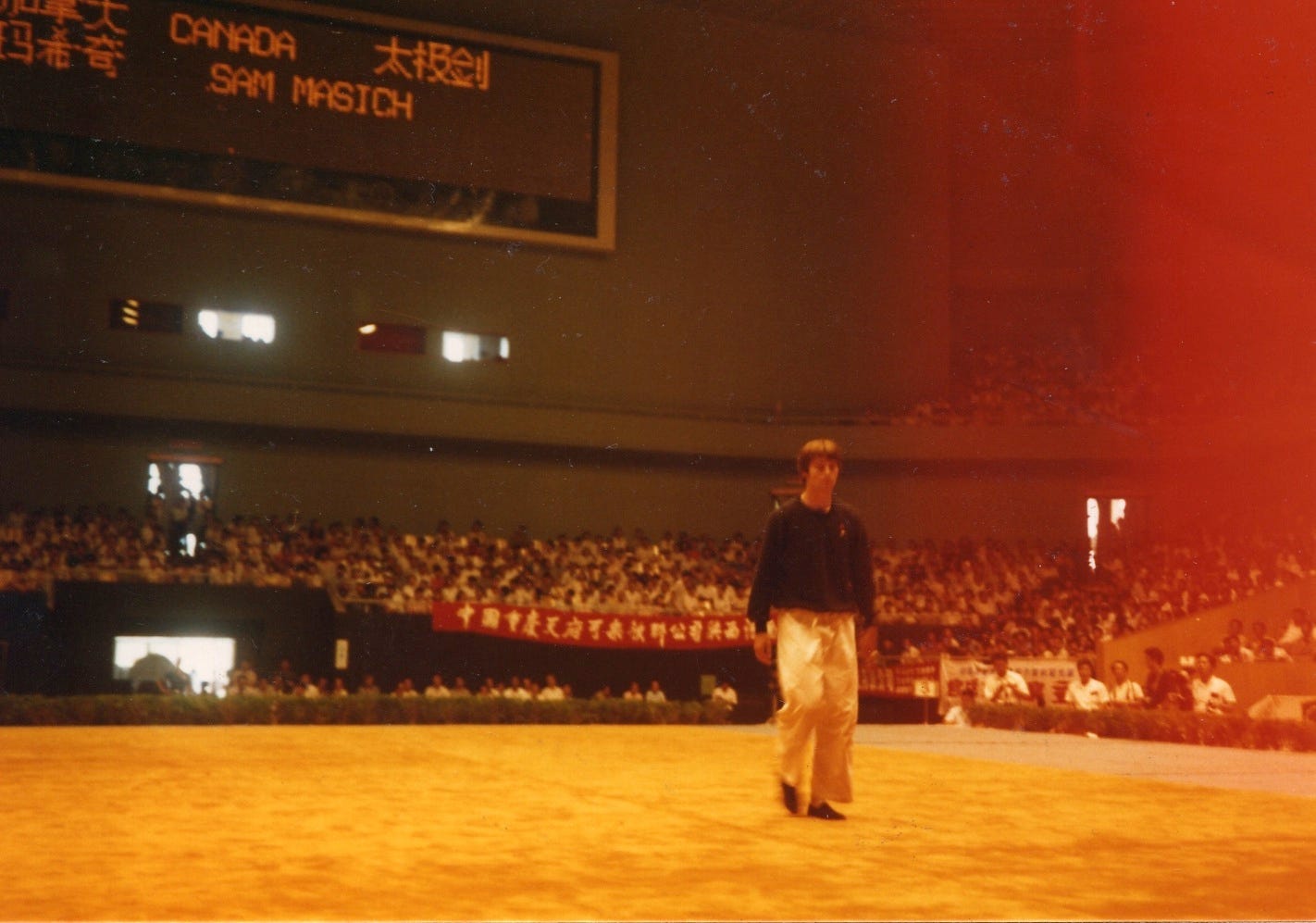

14. Please describe your first Chinese martial-arts competition. How did you fare and what thoughts did you come away with?

Amazingly, the Xi’an world Chinese martial arts championships was my first actual forms competition. For me it was a revelation. I met older generation masters like Sha Gouzheng (沙国政), Gu Liusheng (顧留馨) and Zhang Wenguang as well as mid-generation people like Chen Xiaowang. There were several my-generation wushu stars such as Zhao Changjun (趙長軍) and Zhang Hongmei (張宏梅) as well who were like young gods on springs. Meeting all these people and seeing them do their thing made me feel like my obsession with taiji might not be so strange after all. Where I grew up every kid wanted to be Wayne Gretzky—not Fu Zhongwen.

What I realized after the sword event, was how much standard basic work I still needed to do to match the other competitors. Although I actually knew how to use a sword, I didn’t know how to move with it in way that connected to deeper taijiquan principles and good jian (劍) basics. I think I placed sixth. The day before I was to perform my solo form, I badly twisted my ankle running down a flight of stairs after I’d heard there was a guy selling swords outside the tournament venue. My ankle swelled to about the size of my calf. The Chinese doctor attending me insisted I not put ice on it and rubbed it vigorously, telling me to put all my weight on it immediately. I hid the fact from Master Liang and most of the team because I didn’t want to miss my chance to compete. I was in screaming agony but got to participate in a world championship.

The tournament itself made me realize many things about myself—things I wanted to understand and master. I was shaking uncontrollably when I walked onto the carpet and, for all my practice, was still completely unprepared. For the next three years I dove whole-heartedly into the tournament world in North America. I went to events where there was someone to learn from (e.g. when Master Liang or Dr. Yang were there) and where I could be assured there would be serious judging. Before 1986, when Jeff Bolt promoted the first ever all Chinese martial-arts competition in Houston, Texas, taijiquan or any Chinese martial-art styles tended to be thrown into karate tournaments as an afterthought to get more registration income. All Chinese styles were lumped together in the ‘soft-style’ division. I only competed in tournaments where the officials were qualified to judge Chinese martial arts and especially taijiquan. While I always went in obtain the best possible result, my goal was to master myself, especially my nervousness and fear of being judged. Eventually I was able to overcome this and go onto the competition floor or into a performance environment free of anxiety with the idea of actually sharing something with those witnessing what I was doing.

15. What are your personal views about the benefits of competition?

My competition phase lasted for three years between 1985 and 1988 until Master Liang and Yang suggested I stop in order to allow others the experience of winning and to encourage me to pursue deeper aspects of the training. It can be said without exaggeration that, during the late eighties and early nineties 70% of tournament medalists and national team members in North America had studied to some degree one of or both of these teachers. During that time I became well known as a competitor, especially in 1988 when I was grand-champion in three national-level events. While its true that I grew up in sports family—my father was a track and field coach (the Olympic Games were virtually a religion in our home)—I wasn’t really interested in competition for its own sake or for the sake of winning medals. I was interested in overcoming some personal limitations and improving my overall understanding of taijiquan. Out on the competition ‘circuit’, people thought of me as a modern taiji/wushu type of player and had no idea about my intense training in traditional Yang-style Taijiquan. I did go back on the floor once again in 1994 in an international competition in Shanghai and managed to win seven gold medals.

Even as a serious traditionalist, I recommend the competition experience. Critics of taiji as competition often cite the egotistical nature of the activity as a reason for avoiding it. While there may be truth to this notion, it could also be argued that participation in the art’s performance, portrayal and competitive modes can provide real tests of one’s ability to express the art in situations where one’s ego attachments are made clear. It is one thing to practice ego-less taijiquan in one’s back yard or with doting students and another to deal with personal hangups it in the final match of a push-hands competition or with five judges scrutinizing your every tremor. There is no reason why participating in such activities cannot contribute in the self-cultivation endeavour.

Others spurn competition in favour of no-nonsense, ‘real’ martial arts. However, it might be wise to remember that all martial-arts practices are at best simulations of the real thing. Although the most serious martial training in taijiquan is directed toward the idea of a ‘real fighting situation’ with one or a few opponents, scenarios still tend to exist somewhere in the cracks between martial-contest and martial-combat. The more real things get, the more the rules go out the window and the less relevant formal martial training becomes. When things get most martial, it is flexibility of mind and calmness under pressure that triumphs. If one can’t be cool in the comparatively safe environment of a competition floor it is unlikely one will be at ease when it counts in a real self-defence situation.

Read Taiji in Performance by Sam Masich on Substack

Competitive taijiquan form and push-hands events are organized around the world with varying goals, rules and results. The activity brings together practitioners of the many different schools and styles and offers a possibility for strengthening the art by assisting individual players in furthering their development and by forging bonds for a more cooperative and interactive community. These potential positive benefits, coupled with the popularity of the push-hands game encourage us to think seriously about refining the rules in such a way as to serve future generations of taijiquan practitioners.

It is important to note, that while the push-hands game is widely practiced even by serious taijiquan players, it really exists only outside of what might be defined as ‘traditional taijiquan.’ This form of play does not appear in the records of any traditional taijiquan curriculum nor in any classic writings of past masters. It is just something that taiji people do—and they do it everywhere.

16. How do you introduce your students to push-hands?

The earliest of the twenty-five fundamental jin (勁) or ‘kinetic energies’ in taijiquan is called zhan-nian jin (粘黏勁) or ‘stick-adhere energy.’ It is the foundation upon which taijiquan is built—forms, push-hands drills, weapons, fighting—everything. In my view most of the prevailing approaches to this topic are superficial. People believe they are ‘sticking’ when, in reality, they are ‘following.’ The difference between riding a bike and following behind one, not matter how closely, is whether or not you are actually on the bike. Taiji’s push-hands or tui-shou (推手), as traditionally taught, generally starts with pushing patterns which, while intended to help students develop softness, tend to generate anxiety. ‘Pushing’ as such, can be detrimental to the development of foundational qualities. However, the early energies—stick-adhere energy (zhan-nian jin), listening energy (ting jin 聽勁), comprehending energy (dong jin 懂勁), receiving energy (zou jin 走勁) and neutralizing energy (hua jin 化勁)—have no direct martial intention (as compared to later energies like na 拿, ‘seizing.’)

Unfortunately, the past masters provided no codified or explicit methodology for addressing these early energies. They are usually applied in a patchwork way, conceptually speaking, although they are the fundamental energies required to learn push-hands proper. They are the energetic attributes of what might broadly be described as ‘sensing’ (jue 覺), a term used by Yang Chengfu (楊澄甫) to describe the underlying quality in push-hands.

I therefore use jue-shou (覺手) concepts to get students started on a ‘deep sticking’ path as compared to a ‘shallow sticking’ path. This begins with the clear establishment of the ‘point-of-contact’ via ‘resting-in’ and ‘supporting’ and with the mastery of five ‘operations.’ This provides students with a real method toward mastering the all-important early energies that tend to elude taiji players.

Having established the connection it can now be maintained on the basis of resting-in and supporting. This is done by means of five operations: ‘rolling,’ ‘pivoting,’ ‘transferring,’ ‘inching,’ and ‘exchanging.’ By employing these operations in the maintenance of resting-in and supporting one arrives at a deep ‘stick-adhere energy’ or zhan-nian jin (粘黏勁).

When players base their connection on reaching, grabbing, controlling, thwarting, suppressing, evading, etc., they develop what has been called ‘a slippery style.’ This is what I call ‘shallow’ sticking because, while it’s true that there is a certain degree of connection and sticking, it tends to be a very superficial kind of sticking. If one tries to follow the partner’s movement while simultaneously being driven by his or her own aims, gaps appear and, along with them, much confusion, compensation, and behavioural justification.

17. Central to judo practice is the principle of Seiryoku Zen Yo—‘Maximum Efficiency through Minimal Effort’, which is put into practice through the concept of Ju Yoku Go O Seisu—‘Gentleness Controls Hardness.’ These are akin to the principles of taijiquan. How much of what you learned in judo were you able to apply to your push-hands? How did this influence your success in competition?

This is exactly the principle of taiji. These judo slogans contain language similar to that found in the Taijiquan Classics. In about 1983 I had the opportunity to see Katzuhiko Kashiwazaki (柏崎 克彦) up close in a master class. I was too junior at the time to work with him directly but I saw him hold down 240 pound third-dan black belts when he himself weighed about 145 pounds. He was agile but effortless. He alway found the critical place for control. As we watched him my judo/taijiquan teacher Brien, said to me, “Now thats taiji!”

In Chinese, the slogan seiryoko zenyo is jingli shanyong (精力善用) which means something like ‘vitality well employed.’ While it is often simplistically translated as ‘maximum efficiency,’ it refers to the refinement of naturally-endowed vitality into useful skill in a process by which maximum efficiency is achieved. Ju yoku go o seisu (gang yinde le linghuoxing chang 剛赢得了靈活性常) means something like, ‘the indomitable is overcome by the adaptable’ and infers that it is more important to be clever and mobile than to be strong. It is this mindset that allows the transformation of raw, innate energy jing (精) into shi (勢)—intrinsic power.

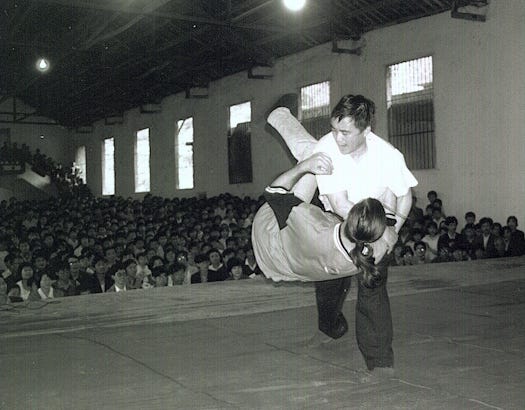

portant way that judo training affected my push-hands was that, because of judo break-fall training (ukemi waza 受け身), I had no fear of falling. I knew how to break my fall and so wasn’t filled with the anxiety that often accompanies loss of balance. Many taijiquan players do not know how to fall or roll and consequently they play a very conservative push-hands games, limited to forcing their partner to lose balance by taking a single, unintended step. The fear of falling can put limits on the development of throwing ability because partners are not able train safely with one another. Throwing is an important part of ‘issuing energy’ (fa jin 發勁) and, while taijiquan throws differ technically from those of judo, the risk of injury during throwing training is similar in both arts. Taijiquan does not have a formal method for teaching break-fall although some schools have integrated the concept into their programs. My first teacher Brien taught me much of my taijiquan on judo tatami mats with full throws and break-falls. Masters Liang and Yang also always had mats around and taught me relationships between taijiquan and Chinese shuaijiao wrestling (摔角).

When I was younger, I supported myself for a short time as a graphic artist and sometimes made comics. One of the characters I created, Joe Judo, gave a tour of the world of judo which appeared in a Canadian judo digest.

18. What changes have you seen in the taijiquan world during your involvement with the art. How would you like to see things unfold from here?

Almost all of the popularization of the art has taken place since the late 1920s. I’ve been around for about a third of that time and have had mentors that have seen most, if not all of it: Master Chung, for example, was born in 1913 and saw firsthand virtually the entire modernization of the art. There are always pros and cons with any evolution.

The best thing I’ve seen during my time in the art is an increase in access. When I first started there were few really good books on taijiquan available and home video had barely emerged. I did and still do cherish my taijiquan library and in my twenties always had a copy of something on me. A tattered copy of Douglas Wile’s ‘Yang Family Secret Transmissions’ lived in my packsack for ten years. I gave a copy to Men Huifeng In 1985 and he was amazed that we knew that much outside of China. It completely changed how he saw me and what he was willing to teach. When I started to learn taijiquan, China had not yet opened. It was a few years later that people like Master Liang Shou-Yu came to North America, opening a portal into the mainland taijiquan world.

Taijiquan scholarship has advanced greatly and we’re constantly learning from translations, teachers, and what new media brings us. The nice thing about being around awhile is being able (usually) to recognize the difference between older variations of the art and newer fads. Taiji-come-lately forms are usually pretty easy to spot. This isn’t always easy though. When I was young I would have gone to almost any length to find out more about Chen-style Taijiquan. Now it’s everywhere—original stuff and new variations. It takes a lot to sort out what’s going on in some areas of the art, Wudang Taijiquan for example. Older players like myself who developed during a period of limited information have our own biases and misconceptions about what’s going on. I think it is more difficult for newcomers though, especially with the conflation of taijiquan with qigong and a general permissiveness around mixing anything together indiscriminately.

Overall, I see potential. In the past, most people who showed talent in movement went to sports like football and basketball or to dance. Now there is enough activity in the taijiquan world to hold the attention of individuals who want to master the art in its fullness. There is a lot of information and opportunity and, if players aren’t too distracted by every new thing coming down the pike, we might see the traditional art thrive rather than drown. My focus is on getting students well prepared and then mentoring them through full-curriculum training. I’d like to see more taijiquan players involved in all aspects of their style—not just a short form, a bit of sword and endless hours of free-style push-hands.

19. You are also a musician. Do you see music and martial arts as having a connection?

Absolutely, there is a connection between my martial-arts practice and my work as a songwriter and musician. First of all, art is art no matter which vehicle is used in its expression. I also draw, paint, and write. Studying taijiquan is a lifelong experience that brings together many areas of human knowledge and endeavour—anatomy and biology, history and politics, sport and health, conflict resolution and performance—all with the aim of unfolding a better, more complete human being.

Taijiquan and martial arts, for me personally, are more about gathering and generating energy whereas music and painting I relate more to expression. Of course martial arts are also expressive and the fine arts can be seen in terms of the energy they cause to coalesce. Many musicians, especially jazz players, play taijiquan as well. The search for a balance between form and freedom is a constant in the artistic quest as is the desire to create through connection. In taijiquan this can be seen in the way patterned but principled movement evolves, starting with set forms and arriving at improvised contact-based movement

20. What's in store for Sam Masich in the future?

I view myself first and foremost as an artist. As a creative person, much of my expression comes through taijiquan. I draw, paint, write, film-make, song-write, perform as a musician, as well as express myself through martial arts. I don’t consider myself particularly talented but I persist until I can do a thing well. In martial arts this tendency expresses itself through teaching and writing. I consider my teaching to be an essential part of the research for my writing and believe it’s important to see what people really respond to and what actually furthers their progress before writing anything definitive about it. This is part of the reason my writing takes such a long time.

Starting a Substack has been an excellent way of transferring some of my many writing projects from my hard drive to an audience and I intend to continue with that. This has helped motivate me to get my first book out—Foundations of Traditional Taijiquan: Core Concepts and Full Curriculum—and motivates me to pursue my rather ambitious writing and publishing goals more diligently.

As of this moment my main writing projects include a two volume overview of the 5 Section Taijiquan (Wuduan Taijiquan 五段太極拳) Program and its philosophy. This is a program I began co-creating twenty or so years ago and which has practitioners around the world. The 5 Section Taijiquan Program is a modular, progressive preparation for the study of traditional taijiquan that focuses on the necessary and sometimes missing building blocks one must have in place if he or she is to truly succeed as a serious taijiquan player. Examples of important fundamentals include: clear core-principles, stance-based form work, sensing-based partner-work in bare-hand and weapons modes as well as bare-hand and sword applications routines. The books I am currently writing will cover all the material in the basic program and make clear how practitioners can save years of training time in their overall goal of mastering traditional taijiquan and get a better result in the process.

The larger goal, publication-wise, is a five volume series on the shisan shi (十三勢) or ‘thirteen powers’ (often incorrectly described as the thirteen ‘postures’) of taijiquan. Past masters deem an understanding of the thirteen powers to be essential in understanding the art. In all my work I try to address what is missing in pedagogy and address the gaps. Today, it is rare to find taijiquan players that are serious in their approach to this fundamental and defining subject. The shisan shi is the basis for all parts of traditional taijiquan curricula—bare-hand, sabre, sword and spear—each with its own thirteen energies collection, yet information on the subject is not widely available and what is out there is woefully incomplete. I feel as the tudi of the two most prolific martial arts authors in the world today, it is my job to honour my teachers by advancing these themes a step or two so that others have something substantial to work with. These and other volumes are meant to form parts of an eventual encyclopedia.