Part One: The Hips

1. Describing the hips

The hip joint is located at the top of each leg and is an articulation that connects the head of the upper femur—the ‘ball’—to the pelvic region at the acetabulum—the ‘hip socket.’ It is referred to anatomically as the acetabulofemoral joint. The ‘ball-and-socket’ structure of the hip joint makes possible a range of complex flexion/extension, abduction/adduction, and rotational actions that change the positional relationship between the thighs and torso. Examples of such movements related to taijiquan include weight shifting between the end positions of stances (when both feet are on the ground) and leg lifting actions such as stepping and kicking (when only one leg is on the ground).

To say that someone ‘moves from the hips’ is not an accurate statement, since the hip joints themselves have no internal mechanism by which to move. Rather, the hip joints are caused to move by a sequence of coordinated actions initiated by muscles in the hip-and-thigh area. The muscles of this region can be divided into four basic groups according to their function and position in relation to the hip joint: the gluteals (buttocks) used in lunging and squatting; the lateral rotators, which rotate the femur to the side and away from the centre of the body; the adductors which draw the legs in toward the midline of the body; and the iliopsoas which provides flexion for standing, walking, and running.

Identifying the ‘hip crease’ or kua

In taijiquan, as with Chinese martial arts study in general, the term kua (pronounced ‘kwah’) is used to describe the area of the inguinal fold, whose movement coincides with articulation of the hip joint. Kua can be translated into English directly as ‘hip’ but especially refers to the inguinal fold or 'hip crease.’ A more specific term, ‘kuà gēn’ (胯根)—the ‘hip root’—is also used in taijiquan literature to describe the joining place where the head of the femur naturally settles into the hip socket.

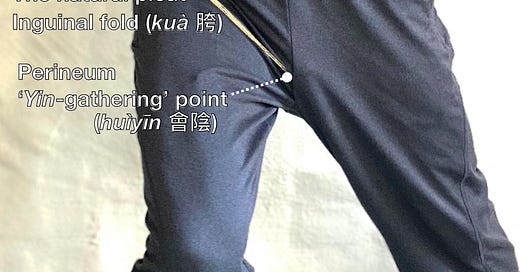

Some early twentieth-century Chinese taijiquan authors use the terms ‘kua’ and ‘kua gen’ interchangeably to describe the inguinal fold. Pertinent expressions by taijiquan instructors include ‘loosen the yao (waist) and the kua’ or ‘sink the qi and settle the kua.’ Similes for kua relate to things that ‘collapse,’ are ‘slung across,’ or that ‘straddle.’ While there is no single word for ‘kua’ in English, the terms ‘hip crease’ or ‘inguinal fold’ adequately describe the kua’s location and function for the purpose of discussing taijiquan. This natural pleat extends diagonally upward and outward from the perineum to where the inguinal ligament meets the anterior superior iliac spine.

The kua is identifiable by the visible diagonal folding of the fabric of one’s pants. The fold of an untucked shirt or jacket, descending from the iliac crest down toward the groin area, serves to illustrate this. ‘Settle into the hip,’ or ‘Relax the kua,’ are instructions given by taijiquan teachers. Most students eventually become accustomed to the Chinese term ‘kua,’ and the word is used commonly by Chinese-speaking and non Chinese-speaking instructors alike, regardless of the classroom language.

The kua and the perineum

While it would seem obvious that there is one kua for each leg, it should be noted that both kua stem from a single point at the perineum, known as the ‘yin gathering’ point (huìyīn 會陰). Recognizing this point as the place of origin for the kua/hip crease on either side makes it much easier to be consistently aware of the full range of movement of the kua as it ‘opens’ and ‘closes.’ Concentrating attention in only the upper part of the kua at the top of the pubis minimizes one’s ability to settle into one’s base of support (a process described as ‘sinking’ or ‘rooting’ by taijiquan players). If one is to develop these skills more deeply and benefit from the full range of movement in the hip joint, one must learn to relax deeply into the kua, all the way to the perineum/huiyin.

2. The aligned ‘hip-track’

Using the thighs of one leg (the ‘driving’ leg) to push the foot of that leg actively down into the ground causes the body to move away from one end of the stance and toward the other. If the hip-area muscles are relaxed during this process, there is no resistance to the force produced by the driving leg and weight will be transferred into the ‘receiving’ leg. One effect of this driving-leg/receiving-leg procedure is that a direct linear path, from one side of the stance to the other side, becomes apparent. This path is called the ‘hip-track.’ Movement and interaction based on taijiquan principles is dependent on practice that is supported by a correctly-aligned hip-track.

The correctly-aligned hip-track can emerge only if the hip joints, knees, and ankles remain in proper dynamic relationship with one another as the ball rotates in the hip socket during weight shifting. There must be no tension in either hip when the receiving leg’s hip joint rotates to accommodate the force. The phrase ‘settling into the hip-track,’ therefore, means ‘relaxing the muscles around the hip joints when weight transfer takes place, so that rotation inside the hip sockets is unobstructed by hip-area muscular tension.’

‘Settling’ or ‘folding’ the kua is a product of the release of muscle tension in the hip region and brings about a proper alignment between the base of support in the feet and the joints of the hips, knees, and ankles. This settled alignment is referred to by taijiquan players as ‘root’ or ‘rootedness’ and is felt as a deep stability and connection with the ground. Under these conditions the hip-track becomes the centre of movement for the kind of weight shifting that takes place within ‘stances.’

Moving through stances

In basic taijiquan practices, weight shifting occurs inside ‘stances’ (bù 步)—standing positions that support the actions for which taijiquan is practiced. Individual stances possess distinctive characteristics and are sometimes known for the shapes they take; the ‘horse stance’ (mǎbù 馬步), for example, resembles the shape legs take when a person is riding a horse; the ‘bow stance’ (gōngbù 弓步) resembles a bent bow and a straight arrow. In a horse stance, the legs are positioned beside one another with space between them, which means the direction of movement of the hip-track is from one side to the other, either left to right or right to left, as rotation occurs in the hip joints. In a bow stance, where one foot is advanced and there is lateral space between the two feet, the hip-track appears to move diagonally. If the right foot is forward, the diagonal path extends from the back and left toward the front and right as weight shifts forward. Variations of these two stances, along with the 'half-horse stance' (bànmǎbù 半馬步), account for most instances of the emergence of the hip-track in traditional taijiquan practice.

Movement errors

Due to the postural demand of staying upright, a degree of tension is always present in the hip-area muscles. It is important that practitioners learn to distinguish between naturally occurring structural tension and unnecessary tightening of the muscles surrounding the hip joints. Movement errors related to excessive hip-area tension are easy to recognize as the pelvis juts obviously out to the side. When it is dropped, as a result of the settling into the hip joint, the pelvis remains naturally aligned with the joints and segments below. Pelvis and hip placement that is not aligned with knees and ankles is ‘out of the hip-track’ and ‘uncentered.’

Another common movement error resulting in incorrect hip-track alignment originates from twisting at the ankles during the transfer of weight. When such twisting occurs, the hip-track becomes incorrectly aligned and compensations are made by the mover that further distort hip-track alignment. Twisting at the ankles is an example of an ‘obstructive behaviour.’ Four paired sets of obstructive behaviours—‘bracing and clenching,’ ‘twisting and torquing,’ ‘augmenting and assisting,’ and ‘holding on and double grabbing’—negatively affect the alignment of the hip-track and contribute to the ‘four errors’ identified in early taijiquan literature. It takes great patience to recognize the sources of the obstructive behaviours and to bring them under control.

‘Clear’ hip joints

Rotation that occurs as a direct consequence of pressure from the driving leg takes place not only in the receiving leg’s hip joint but also in the hip joint of the driving leg. When the muscles around the hip joints remain largely without tension, both hip joints can rotate freely and thereby contribute to a correctly-aligned hip-track. It can then be said that the hip joints and kua are ‘clear.’

‘Clear’ hip joints acquiesce to pressure, allowing force, movement, and kinetic energy to transfer through them. Forces that generate movement through the hip-track may come either from within one’s own structure, such as the pressure exerted by a driving leg, or from an external source—for instance, from pressure applied by a push-hands (tuīshǒu 推手) partner. One additional advantage of this transferring from one ‘clear’ kua to the other is that the legs are strengthened in a unique way since the thighs function both to drive the movement and to receive the shifted weight.

Alignment of the ankles and the knees

The ankle joint is the juncture between the leg and the foot and consists of three bones held together by several ligaments. The structure of this articulation mainly facilitates movement in the form of dorsiflexion (the top of the foot is brought toward the shin) and plantar flexion (the top of the foot moves away from the shin). The ankle also allows a small degree of rotation and side-to-side movement; however, it is relatively easy to over-rotate and injure the joint. Over-rotating the ankle, or ‘twisting,’ especially during plantar flexion, is a main cause of strained and sprained ankles. These intrinsic structural limitations in the ankle joint make it possible to strain not only the ankles and but also the knees, which take up the stress once the ankle’s range has been breached.

The knee is a hinge joint whose primary function is flexion and extension between the upper and lower leg. It is even more restricted than the ankle when it comes to side-to-side movement. Although the ankle’s rotational capacity makes it possible for the kneecap to point inward, ideally the kneecap should remain oriented in the direction to which the foot is pointed to allow the entire leg optimal structural stability. Over-rotation of the ankles and knees during leg-weighted dorsiflexion can compromise the knee alignment and cause strain, as when in a taijiquan movement one shifts to the back leg while twisting the rear-leg ankle inwards.

Thigh development

It is important to recognize that the thigh-area muscles are some of the biggest muscles in the human body and are perfectly designed for the kind of loading found in taijiquan practices where there is an ongoing alternation between driving through one thigh and receiving into the other thigh. The weight shifting movements in taijiquan generally employ the quadriceps of the driving leg. These muscles are activated when standing up from a squatting position or in the downward ‘loading’ action preliminary to jumping. The gluteus maximus and adductors play a strong role in lunge-like weight shifting. When flexed, all these muscles can restrict freedom of movement in the hip joint, therefore, in stance work based on a correctly aligned hip-track, these muscle groups are purposely left relaxed.

Because the practice of minimizing hip-area muscle involvement necessitates that the quadriceps of the receiving leg bear much of the burden of the shifted weight, taijiquan practitioners who maintain a correctly-aligned hip-track develop strong quadriceps and a keen sense of balance.

In an effort to avoid discomfort in the thighs, many players clench the gluteus maximus and adductors, as this activation relieves pressure from the quadriceps. Training the legs in taijiquan requires maintaining relaxation in the hip region and developing a tolerance for discomfort in the thigh muscles as they strengthen. Many taijiquan masters advocate the practice of ‘standing post’ (zhàn zhuāng 站樁) body alignment exercises that strengthen the quadriceps and inure students to the inevitability of aching thighs.

3. Functions of the hips and kua

From their location near the centre of the body, the hip-area muscles and hip joints perform several functions simultaneously. As large physical structures connected to the upper legs and pelvis, the muscles serve to support upper body weight; the rotating hip joints facilitate movement; and the hip-track transfers power. It is important that the muscles surrounding the hip joints remain free of tension so that all of these effects can be realized.

The ‘channeling hip’

The weight of the upper body passes down through the settled hip joints directly into the thighs, creating conditions in which the legs and torso align themselves with one another and with gravity. Since the muscles that make up the quadriceps are some of the largest and the strongest muscles in the body, they are ideal for supporting the upper body’s weight, leaving the torso free for action. Channeling the upper body’s weight down through the kua into the supporting thighs is therefore one of the most important roles of the hip joint, especially when movement occurs between the various stances of taijiquan routines. Without correct ankle, knee, and hip joint alignment, and without tension-free muscles in the hip region, the body’s weight, instead of being sustained principally by the thigh muscles, is distributed ineffectively across other muscle groups that are not designed primarily for structural support. This lateral spreading of tension demands types of exertion that are incompatible with the objectives of taijiquan and leads to a subtle, ever-present physical tension and anxiety that results in many kinds of errors. The resulting strain restricts mobility and creates barriers against connected, supported movement. Incorrect hip alignment also puts undue stress on the knees, further restricting movement and potentially causing pain and injury.

The ‘carrying hip’

When weight is shifted from one side of a stance to the other, the upper body remains undisturbed—as long as it is carried by movement that follows a correctly-aligned hip-track. Carried movement of the torso and head is smooth and steady when the receiving hip joint passively rotates in response to the force introduced by the driving leg. Without a smooth translation of forces, made possible by relaxation in the muscles around the hip joints, a confused energy possesses the legs, which then require ongoing compensatory assistance from the arms, buttocks, torso, and feet. When the hip joints are ‘clear’ and movement through the hip-track is correct, the upper body is carried comfortably while the weight shifts securely to and fro.

The ‘transferring hip’

The hip joints, when loose and settled into their natural position, provide a conduit through which power from the legs is mediated upward into the torso to be directed by the waist. Hip joints unobstructed by muscular tension in the surrounding region allow the force of the legs to pass to the upper body unhindered. This is part of the meaning of the following line from ‘The Taijiquan Classic’ (Tàijíquán Jīng 太極拳經).

Its root is in the feet; issued through the legs; directed from the waist; goes out from the fingers.

If the hip joints are affected by surrounding muscle tension, power will be bound and prevented from its upward journey through the waist and beyond. The kua is concerned with both the shifting of weight in the legs and the delivery of power. The hip joint simultaneously performs the functions of transferring force upward, receiving incoming force, passing the weight of the upper body into the thighs, and shifting through the hip-track.

Above is Part One of Chapter 5, “Understanding the Hips and Waist,” from Foundations of Traditional Taijiquan: Core Concepts and Full Curriculum by Sam Masich.

In ‘Part Two: The Waist,’ the waist, waist movement, and functions of the waist are discussed. ‘Part Three: Hip-and-waist errors’ delves into the ‘four errors’ (sìbìng 四病) found in classical taijiquan literature. These will be available for Paid Subscribers.