In 1985, I represented Canada at The First World Wushu Invitational Tournament in Xi’an, China. When I returned to Canada, I was a changed person—at least as far as my perspective on Chinese martial arts was concerned. Until this point, I’d only experienced Yang-style Taijiquan but was now eager to learn Chen-style Taijiquan.

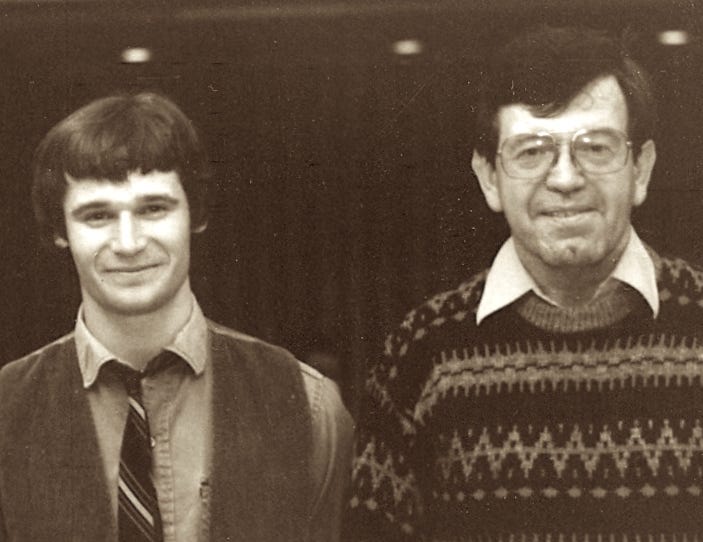

When I returned from Xi’an, my teacher Brien Gallagher expressed curiosity about my trip and we discussed the entire experience in detail over many training sessions, dinners, and beers. I described the many curious things I’d observed and he listened intently asking few questions and usually only weighing in when I described my push-hands experiences. He noticed I’d learned some Chinese and was impressed by this but showed little interest in my descriptions of the wushu form demonstrations that I’d seen. He seemed especially intrigued with my stories of Master Liang and could see clearly that I was enthralled by this newcomer to the Vancouver martial-arts scene.

In China, Master Liang had introduced me to his friend Master Chen Xiaowang, the nineteenth-generation lineage holder of Chen-style Taijiquan, and we had all gone on a sightseeing tour together along with other Canadian team members. After meeting the Chen master, I really wanted to learn Chen-style Taijiquan from him and had concocted a plan—I would learn as much as I could from Master Liang and sometime in the future ask him to arrange for me to study with his friend the great Chen master.

After explaining everything to Brien I asked him what he thought about studying with Liang Shou-Yu. His response was simple. “No, that’s not a good idea,” he said.

“But Master Liang is really great,” I argued. “His Chen-style is amazing, and Chen is the basis for everything we do in the Yang.”

I was quite upset at Brien’s stance on the subject. I thought it narrow minded and controlling. Almost immediately, the types of thoughts I’d had in the past about him ‘not letting me do things’ resurfaced:

“Brien is being controlling. He doesn’t understand how good the martial arts are in China. I’ve actually been there. He feels threatened by Master Liang. It’s not fair!”

This was very difficult to accept.

Brien had always tolerating me arguing with him during situations where I disagreed—even to the point, on a couple of occasions, of me throwing tantrums. We had many themes of ongoing disagreement but he put up with this, pretty much always sticking to his point. Basically, he’d just let me play myself out. My reaction to him telling me I could not go study with Master Liang was pure petulance. Over the next weeks I brought it up several times again and every time he just said, “No.”

The first Sunday of the new year in 1986, some four months after China, I arrived at Brien’s place for our weekly training session. As I was stretching, Brien said, “Today you start the Chen.”

I looked at him blankly.

“Just follow,” he said.

I did as I was told and he taught me the first movements the ‘Chen-style Taijiquan Old-frame First-routine’ (Chenshi Taijiquan Laojia—Yilu 陳式太極拳老架一路).

After an hour or so, he said, “Now practice that,” and went upstairs. Another hour later he came downstairs. “Let’s take a look.”

He made a few corrections. “Do that fifty times this week,” he said and we carried on with our normal practice.

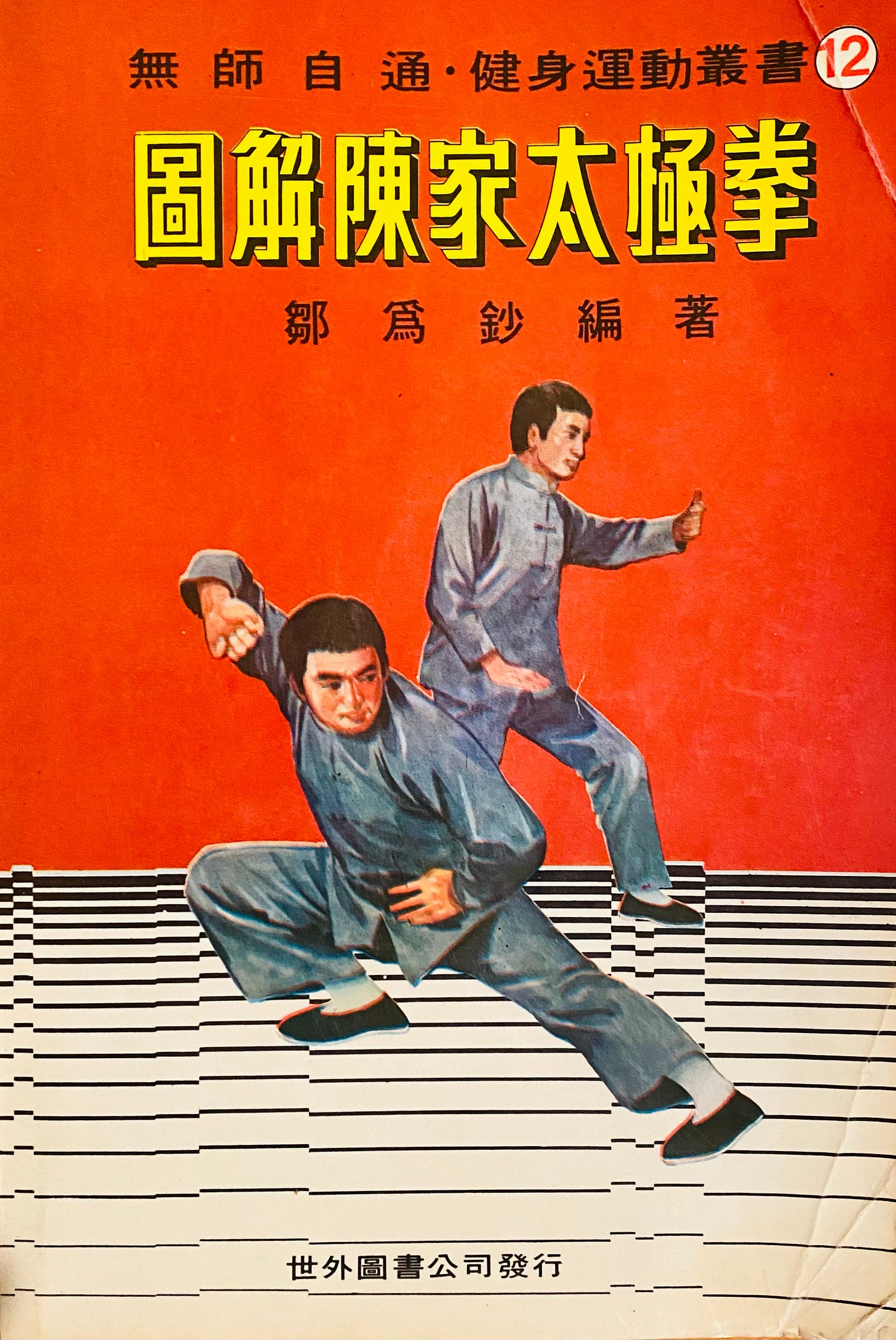

Over the next few months, he continued teaching me the routine, occasionally referring to a Chinese book on the subject. Every Sunday, usually about four o’clock in the afternoon, Brien would say, “Well, I guess I’ll put on the roast.” Then he’d go upstairs and prepare a roast beef in the oven for dinner while I’d continue practicing on my own in the judo room. I’d pour over the photos in the Chen book, looking for clues for improvement.

I scoured the Chinatown bookstores and found a copy for myself and scrutinized it constantly. The next week I’d point out inconsistencies, essentially arguing with him over things I thought were incorrect—so embarrassing to think about now.

For several months, I worked hard on the Chen, practicing several hours daily and trying to perfect every movement he showed me. Gradually, I came to grasp how every movement was related to the ones in the Yang-style Taijiquan long form—how Chen was the parent form of Yang, something I’d read about but hadn’t really understood.

When we finished the form, Brien congratulated me commenting that it was looking very good. I was extremely proud of myself, “None of Master Chung’s other students had been taught the Chen form,” I told myself.

Then, I asked Brien, “Where did you learn it? From Master Chung?” I had assumed this since Master Chung also knew Wu-style Taijiquan and thought maybe he knew the Chen as well.

“No,” he said. “I taught it to myself from this book.” Suddenly I became a little concerned, “Well, how do you know the transitions are correct?” I asked.

Then, he explained to me what he’d been doing for the past seven months.

Every lunch hour, at his place of work, he’d take half-an-hour to get the gist of the movements. Then, on Saturdays at the Vancouver Tai-Chi Chuan Association, he would ask Helen Chung, Master Chung’s wife and a veteran practitioner of the Chen-style Taijiquan, to correct him in his postures and transitions. When he’d finished learning the form after four months, he began teaching it to me in the judo room—all-the-while maintaining his lunch hour and Saturday sessions with Helen Chung.

“Your questions were very helpful,” he said. “If I didn’t know how to answer them I’d check with Mrs. Chung.”

He told me he’d learned a lot in the process and suddenly I felt quite ashamed of myself for my challenging attitude.

Due to my participation on the Canadian national team and for a few other ways I’d participated in the Vancouver Chinese martial-arts scene, I’d been invited to join an association of local instructors who were holding an annual banquet in a downtown hotel one Saturday evening. There I met Master Liang, who was also a member of the association, and we reminisced a little about China. At some point I asked him if I could learn Chen-style Taijiquan with him. He said, “You are very good at Yang-style Taijiquan already, no need learn Chen.”

“But, I’d really like to learn from you. After I saw you do the Chen form in China I thought about it many times,” I persisted.

“Really?” he said. “What your teacher say? Many times, students want to learn from me, make their teacher angry.”

“Well, I can ask him,” I moped, thinking I’d hit that same permission wall again.

“You ask, maybe come my classes, each week two classes Chen-style Taiji,” he informed me.

“Master Liang, when I learn with you I don’t really want to come to your classes. I want to learn from you privately,” I appealed.

“You should learn the form first in my school,” he replied.

“But I already know the form,” I countered.

“Really? Okay, you show me,” looking a little amused.

There in the hotel lobby I started, crouching as low as I could go, stamping my feet as hard as possible. With each movement there was only one thought—“Impress him!”

After my overwrought performance, he said, “You did very good... I think you don’t need to learn from me.”

Crestfallen, I replied, “C’mon Master Liang, please. I know I’m not good yet and I really want to learn to move like you do.”

He looked at me like a parent looks at a pleading child and laughed, “Okay, you ask your teacher if it’s okay.”

The very next morning, in the judo room, I nervously began speaking with Brien about the banquet, the performances, the Chinese martial-arts politics, and especially about my conversation with Master Liang. I told him that I’d demonstrated the Chen long form for him in the hotel lobby.

“What did he think?” Brien asked.

“He said it was good. And he offered to help me improve it, but only if it’s alright with you.” I felt a sudden wave of deja vu.

Without hesitation, Brien replied, “Sure.”

“Are you sure that’s okay?” I asked, astonished.

“You’re ready now,” he said.

He explained to me that if I’d gone to work with Master Liang six months before the master would not have taken me seriously—that I would have been stuck in the back of the class. “Now he’ll pay attention to you. He’ll see the Sam that I see.”

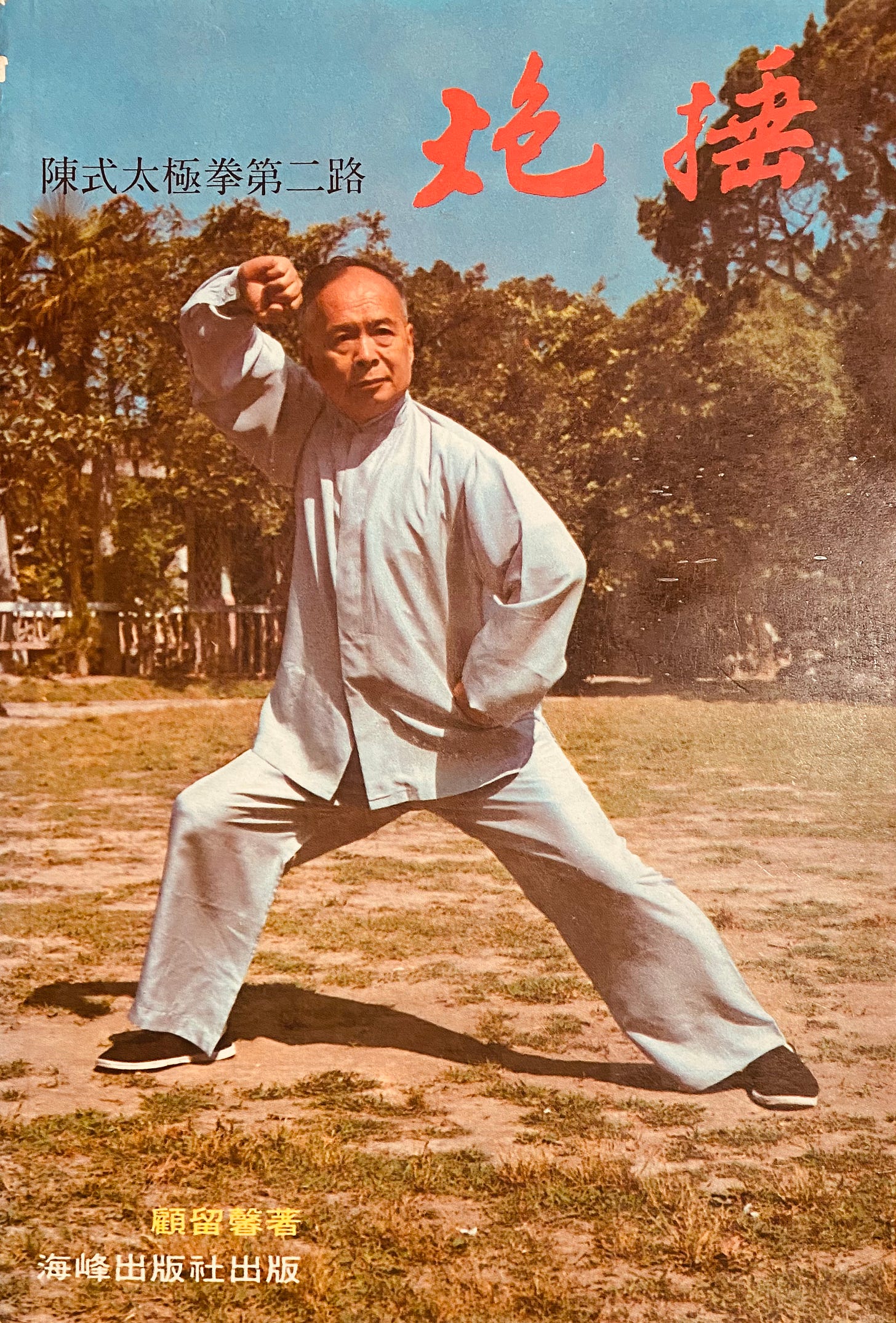

I went on to relearn the Chen first routine with Master Liang and, as well, the famous Chen-style Taijiquan ‘Second routine’ (Chenshi Taijiquan erlu 陳式 太極拳二路), better known as ‘Cannon Fist’ (pao chui 炮捶) that Master Liang had learned from Master Gu Liuxin who was famous for the routine in China.

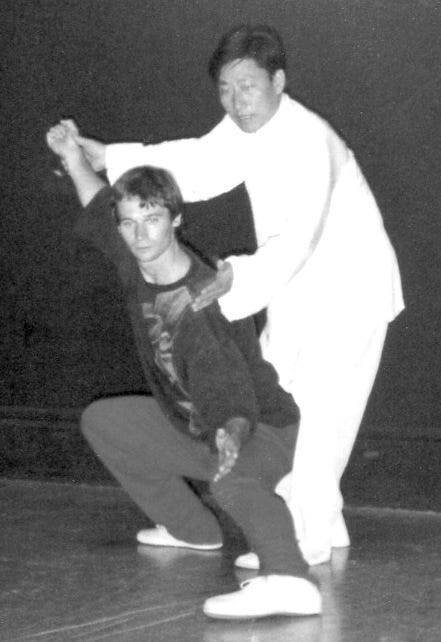

Over time, I learned the Chen push-hands curriculum and the Chen sword, and before Chen Xiaowang finally came to North America for the first time in 1988, Master Liang contacted him and said, “Take care of my very good student Sam Masich.”

Chen Xiaowang, remembered me from Master Liang’s introduction in China in 1985 and used me as his demonstration partner for five days in Winchester, Virginia and then as group leader for three more in San Francisco, California. I worked with many other Chen teachers over the years and, while Chen is not my first interest, developed a short version of Chen-style for The 5 Section Taijiquan Program based largely on my work with Chen Xiaowang and Master Liang.

Brien never did the Chen form again. He’d only learned it to help me get a foot in the door with these other great masters.

Two decades later, Brien and I were reflecting on this period. I asked him what motivated him to take such great care of me and my martial-arts education.

He said to me, “From the beginning I spotted that you were a real teacher—but that you had nothing to teach.”

After forty-five years I continue to try to master his lessons both as an internal-arts practitioner and as a human being.

A loner by nature, good in his own company, and always working to master his interests—whether they be martial-arts related, or any one of the seven Celtic instruments he taught himself play—Master Patrick Warren Brien Gallagher has, given the world of taijiquan to me—¸and me to the world of taijiquan.

I cannot imagine a more generous teacher and mentor.

Really nice. Sam… can I learn Sun style? 😅

What a wonderful story my friend. Thank you for sharing it.