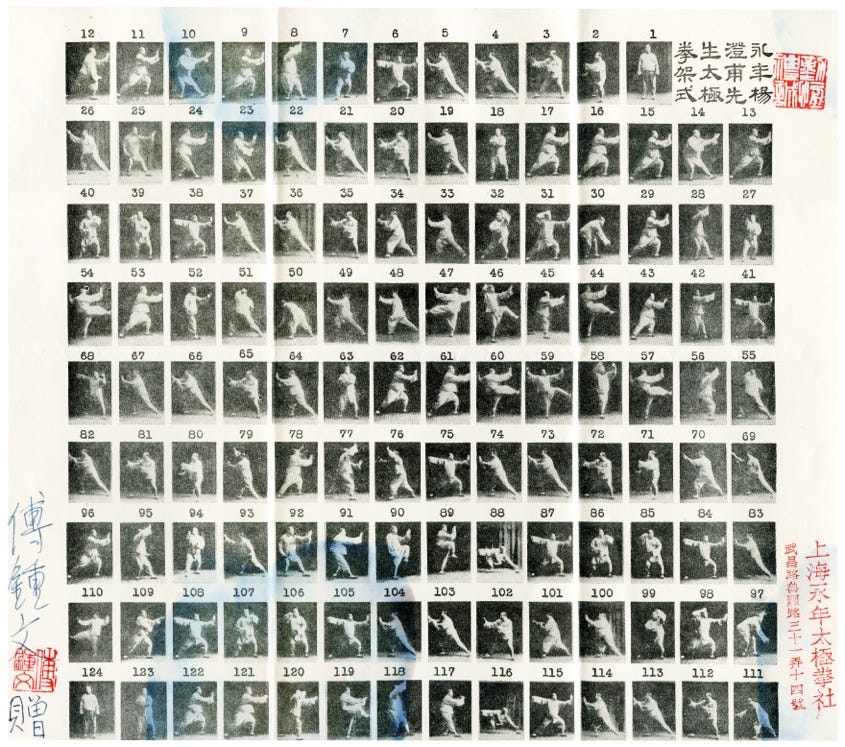

Yang Chengfu,1 the third-generation inheritor of the Yang-family Taijiquan tradition, is generally credited with making the art widely accessible through his public instruction and his books. Yang ’s variation of his family’s ‘long-fist’ solo-barehand sequence—characterized by slow, large, round, and continuous movement—provides the image for what most people now associate with taijiquan.

Living in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou between 1914 to 1934, Yang travelled and taught widely in China. As well as teaching in his various places of residence, he disseminated his art in Wuhan, Nanjing, Hankou, Hangzhou, and several other cities. In 1928, at its founding, Yang Chengfu was invited to be the principal taijiquan instructor of the highly-influential, government-sponsored martial arts establishment The Nanjing Central Guoshu Institute.

Originally narrated by Yang Chengfu to Zhang Hongkui (张鸿逵), ‘The Practice of Taijiquan’2 first appeared in print in Yang Chengfu’s (楊澄甫) second book, The Complete Book of Taijiquan Theory and Practice.3 This highly useful text has guided Chinese Taijiquan masters for nearly one-hundred years and is arguably as influential on the practice of the art as have been the Taijiquan Classics4 themselves. The original Chinese text can be found in the footnotes below.

The Practice of Taijiquan (太極拳之练习谈) by Yang Chengfu (楊澄甫)

Since ancient times there have been an abundance of schools promoting Chinese wushu.5 Each is alike in that successive generations have devoted great effort—striving to resolve technical skills with theory and philosophy—but few have really succeeded.

If a student makes an effort to put in a day of practice, he or she gains the achievement of just that one day of work. But over months and years one may accumulate expertise naturally. As the saying goes, “Falling raindrops, if they fall constantly, will bore through a stone.”

Part of the rich cultural heritage of China, taijiquan is an art whose slow, soft forms disguise great power—this is well encapsulated in another time honoured saying, “Inside cotton, a hidden needle.” The technical, physiological, and mechanical principals are, in fact, rooted in a philosophy.

Those who aspire to mastery must go through definite stages for an appropriate length of time and, although guidance from a quality instructor and exchange with friends are necessary, the critical element is regular daily practice. One can discuss and analyze all day long, contemplate for years and yet, still lacking the gong fu necessary to overcome an adversary, remain like a beginner without even one day’s accomplishment. Men and women, young and old, if they train morning and evening, through hot and cold, without breaks and exceptions, will be successful. Indeed, the ancients said that it is ‘wiser to practice than to ponder,’ and learners of taijiquan, men and women, young and old, will get the best possible results if they keep at it all the year round.

Now, from north to south, from the Huang to the Chang rivers,6 great numbers of people are taking up the study of taijiquan and this bodes well for the future of wushu! We do not lack for acolytes but, while many of these enthusiasts possess boundless potential and train in a thoughtful and dedicated manner, most nevertheless fail to avoid two common pitfalls. The first involves particularly talented, perhaps younger or stronger individuals, who grasp basic skills and concepts quickly but grow complacent and bored before reaching a truly high level of skill and understanding. Though they initially surpass their classmates, later they do not succeed.

The second issue befalls individuals who, anxious to progress rapidly, try learn everything—barehand forms, straight-sword, sabre, spear—within a short space of time. Although they can ‘paint a gourd by copying a pattern,’ the flaws—in their direction and sequencing; upper and lower body coordination; balance between inner and outer—are immediately apparent to the expert. To correct their practice, every form needs to be rectified—although what has been repaired in the morning will be spoiled again by the evening. In wushu circles we say, ‘Learning taijiquan is easy; correcting it is difficult.’ The point is: people try to learn too quickly and delude themselves and others. Their mistakes are passed on to future generations and great harm is done to the art.

In the initial study of taijiquan, one must first learn the ‘Boxing Form’7 posture-by-posture, according to the curriculum, minding carefully the instructor’s every posture and gesture. When ‘studying the form,’ pay attention to the ‘nei,’ ‘wai;’ ‘shang,’ ‘xia’ (inner, outer; above, below).8 ‘Nei’ suggests mindfulness rather than the use of clumsy force. ‘Wai’ refers to the nimble movement achieved by relaxation of the outer limbs, the shoulders and the elbows; also to sequencing movement from the feet to the legs to the waist in a soft and continuous fashion. ‘Shang’ advises emptying the neck to allow energy to reach the head-top,9 while ‘xia’ means sinking the qi to the dantian.10 Novices should reflect on these important guidelines day and night until they are memorized and deeply understood. During practice, persistently correct each form and gesture without looking for shortcuts or instant results. Slow and steady progress will guarantee long term benefits. Avoid violating the principles early on and there will be little or nothing to correct later.

Do not constrain the breath with mouth and belly tension. Keep the joints of the body relaxed, allowing unconstricted and natural gesture. While these ideas are often expressed by internal martial-arts11 practitioners but as soon as they start to move—turning the body, kicking the legs or twisting the waist—their breath becomes heavy and their stepping staggers. This defect results from holding the breath and overexertion.

Practitioners should observe these points:

1. Keep the head erect, inclining it neither forward nor backward. There is an expression: ‘As if something sits on your head; careful not to let it fall.’ Avoid stiffening the neck however, instead ‘suspend,’ so that the eyes, while looking levelly forward, follow the turning of the body. Though the eyes seem to gaze into emptiness, they are actually a very important component in ‘whole-body movement’ and in overcoming insufficiencies in hand and body methods. The mouth is slightly open, yet slightly closed. Inhale through the nose, exhale through the mouth, breathing naturally. If saliva is secreted from below the tongue, swallow it rather than spitting out.

2. Maintain an upright torso; keep the spine and tailbone12 vertical. As movements open and close, the chest sinks slightly, the back opens and the shoulders relax, allowing the waist to turn flexibly. Beginners must adhere to these guidelines, otherwise, in spite of long years of practice, their actions will become rigid and lifeless and the benefit will be limited.

3. The joints of the arms must loosen,13 allowing the the shoulders to sink and the elbows to drop. The palms extend slightly with the fingertips slightly bent. The yi mobilizes qi into the fingers. As the benefits of practice accrue over time, internal energy consolidates and becomes lively and bringing forth unusual abilities.

4. Step like a cat, carefully distinguishing empty and full. When one leg is firmly weighted, the other is described as ‘empty.’ If weight is shifted to the left, the left is full and the right is empty. If shifted to the right, the right is full and the left is empty. However, the leg described as ‘empty,’ is not completely without substance: it still possesses residual intention and the potential for extension and contraction. The ‘full’ leg is firmly settled but not caused to exert strenuously. If one over-exerts or over-extends the leg, the torso will be caused to lean forward, resulting in a loss of balance which creates defensive vulnerabilities.

5. There are two basic types of kicking: upward left and right open-toe separating kicks14 and downward left and right sitting-heel rising kicks. In the first, pay attention to the tip of the foot; whereas in heel-kicks, pay attention to the entire sole of the foot. To wherever the yi is mobilized, the qi extends and the jin follows.15 The joints must be relaxed and open if one is to kick with stability and power. Here one is especially likely to over-exert or bend forward, destabilizing the body and weakening the kick.

Learning taijiquan begins with the taiji bare-hand form or ‘long-fist.’ This is followed by: ‘Single hand push-hands method,’ ‘Fixed-step push-hands method,’ ‘Active-step push-hands method’, ‘Large roll-back,’ ‘Sparring,’ ‘Taiji straight-sword,’ ‘Taiji sabre,’ ‘Taiji spear’16 and so forth.

Practice regularly, ideally twice in the morning and/or twice before bedtime—if possible, practice seven or eight times throughout the day. At the least, practice once in the morning and once at night.

The best places to practice are open courtyard gardens or large rooms with good air circulation and plenty of natural light. Avoid practicing while facing strong wind or in dark, damp, or dirty places, especially those with poor air quality, as the breath naturally deepens during practice and harm to the lungs or illness could occur. Avoid practicing immediately following a large meal or after drinking alcohol. Wear loose, comfortable, natural clothing and good fitting cloth shoes. If perspiring during practice, do not take off too much clothing or rinse with cold water so as to avoid catching cold.

Original Chinese text17

Yang Chengfu Yang Chengfu (楊澄甫; 1883–1936)

Literally ‘Taijiquan Practice Talk’ (太極拳之练习谈)

Taijiquan Tiyong Quanshu (太極拳體用全書)

(Taijiquan Jing 太極拳經)

Chinese martial arts (wushu 武术).

Yellow River (Huang He 黄河). Long River (Chang Jiang 長江); known as the ‘Yangzi’ or ‘Yangtse’ River in English.

Literally the ‘fist frame’ (quan jia 拳架). Often referred to as the ‘Taiji Long Boxing Form’ (taijichangquan taolu 太極長拳套路).

‘inner’ (nei 內); ‘outer’ (wai 外); ‘above’ (shang 上); ‘below’ (xia 下).

ʻEmpty Neck, Raise Spirit’ (xu ling ding jin 虛領頂勁).

‘Vital energy’ (qi) sinks to the ‘centre’ (dantian)—(qi chen dantian 氣沉丹田).

(neijiaquan 內家拳)

coccyx (weilu 尾闾)

(song 松)

‘Separating Foot’ or ‘Parting Kick’ (fen jiao 分脚). Lifting Foot’ or ‘Rising Kick’ (qi jiao 起脚)

yi (意) ‘will’; ‘intention.’ qi (氣) ‘vital force.’ jin (勁) ‘intrinsic force.’

‘Single hand push-hands method’ (dan shou li yuan tuishou fa 單手立圓推手法); ‘Fixed-step push-hands method’ (ding bu tuishou fa 定步推手法); ‘Active-step push-hands method’ (huo bu tuishou fa 活步推手法); ‘Large roll-back’ (dalü 大扌履); ‘Sparring’ (sanshou (散手); ‘Taiji straight-sword’ (taijijian 太極劍); ‘Taiji sabre’ (taijidao 太極刀); ‘Taiji spear’ (taijiqiang (太極槍).

太极拳之练习谈 (李雅轩的师傅杨澄甫先生口述,张鸿逵笔录)

中国之拳术,虽派别繁多,要旨皆寓有哲理之技术,历来古人穷毕生之精力,而不能尽其玄妙者,比比皆是。学者若费一日之功力,即得有一日之成效,日积月累,水到渠成。

太极拳,乃柔中寓刚、棉里藏针之艺术,于技术上、生理上、力学上,有相当之哲理存焉。故研究此道者,需经过一定之程序与相当之时日,虽然良师之指导、好友之切磋,固不可少,而最紧要者,是在逐日自身之锻炼。否则谈论终日,思慕经年,一朝交手,空洞无物,依然是门外汉者,未有逐日功夫。古人所为,终思无益,不如学也。若能晨昏无间,寒暑不易,一经动念,即举拳练,无论老少男女,及其成功则一也。

近来研究太极拳者,由北而南,同志日增,不禁为武术前途喜。然同志中,专心苦练,诚心向学,将来不可限量者,故不乏人,但普通不免入于两途,以则天才既具,年力又强,举一反三,颖悟出群,惜乎稍有小成,便是满足,邃迩中辍,未能大受;其次急求速效,忽略而成,未经一载,拳、剑、刀、枪皆已学全,虽能依样葫芦,而实际未得此中三昧,一经考究其方向动作,上下内外,皆未合度,如欲改正,则式式皆须修改,且朝经改正,而夕已忘却。故常闻人曰:“习拳容易改拳难。”此语之来,皆由速成而至此。如此辈者,以误传误,必致自误误人,最为技术前途忧者也。

太极拳开始,先练拳架。所谓拳架者,即照拳谱上各式名称,一式一式由师指教,学者悉心静气,默记揣摩,而照行之,谓之练架子。此时学者应注意内外上下:属于内者,即所谓用意不用力,下则气沉丹田,上则虚灵顶劲;属于外者,周身轻灵,节节贯串,由脚而腿而腰,沉肩曲肘等是也。初学之时,先此数句,朝夕揣摩,而体会之,一式一手,总须仔细推求,举动练习,务求正确。习练既纯,再求二式,于是逐渐而至于习完,如是则毋事改正,日久亦不致更变要领也。

习练运行时,周身骨节,均须松开自然。其一,口腹不可闭气;其二,四肢腰腿,不可气强劲。此二句,学内家拳者,类能道之,但一举动,一转身,或踢腿摆腰,其气喘矣,起身摇矣,其病皆由闭气与起强劲也。

摩练时头部不可偏侧与俯仰,所谓要“头顶悬”,若有物顶于头上之意,切忌硬直,所谓悬字意义也。目光虽然向前平视,有时当随身法而转移,其视线虽属空虚,亦未变化中一紧要之动作,而补身法手法之不足也。其口似开非开,似闭非闭,口呼鼻吸,任其自然。如舌下生津,当随时咽入,勿吐弃之。

身躯宜中正而不倚,脊梁与尾闾,宜垂直而不偏;但遇开合变化时,有含胸拔背、沉肩转腰之活动,初学时节须注意,否则日久难改,必流于板滞,功夫虽深,难以得以致用矣。

两臂骨节均须松开,肩应下垂,肘应下曲,掌宜微伸,手尖微曲,以意运臂,以气贯指,日积月累,内劲通灵,其玄妙自生矣。

两腿宜分虚实,起落犹似猫行。体重移于左者,则左实,而右脚谓之虚;移于右者,则右实,而左脚谓之虚。所谓虚者,非空,其势仍未断,而留有伸缩变化之余意存焉。所谓实者,确实而已,非用劲过分,用力过猛之谓。故腿曲至垂直为准,逾此谓之过劲,身躯前扑,即失中正姿势。

脚掌应分踢腿(谱上左右分脚或写左右起脚)与蹬脚二式,踢腿时注意脚尖,蹬腿时则注意全掌,意到而气到,气到而劲自到,但腿节均须松开平稳出之。此时最易起强劲,身躯波折而不稳,发腿亦无力矣。

太极拳之程序,先练拳架(属于徒手),如太极拳、太极长拳;其次单手推挽、原地推手、活步推手、大捋;再次则器械,如太极剑、太极刀、太极枪(十三枪)等是也。

练习时间,每日起床后两遍,若晨起无暇,则睡前两遍,一日之中,应练七八次,至少晨昏各一遍。但醉后、饱食后,皆宜避忌。

练习地点,以庭院与厅堂,能通空气,多光线者为相宜。忌直射之烈风与有阴湿霉气之场所,因身体一经运动,呼吸定然深长,故烈风与霉气,如深入腹中,有害于肺脏,易致疾病也。练习之服装,宜宽大之中服短装与扩头之布鞋为相宜。习练经时,如遇出汗,切忌脱衣裸体,或行冷水楷抹,否则未有不患疾病也。