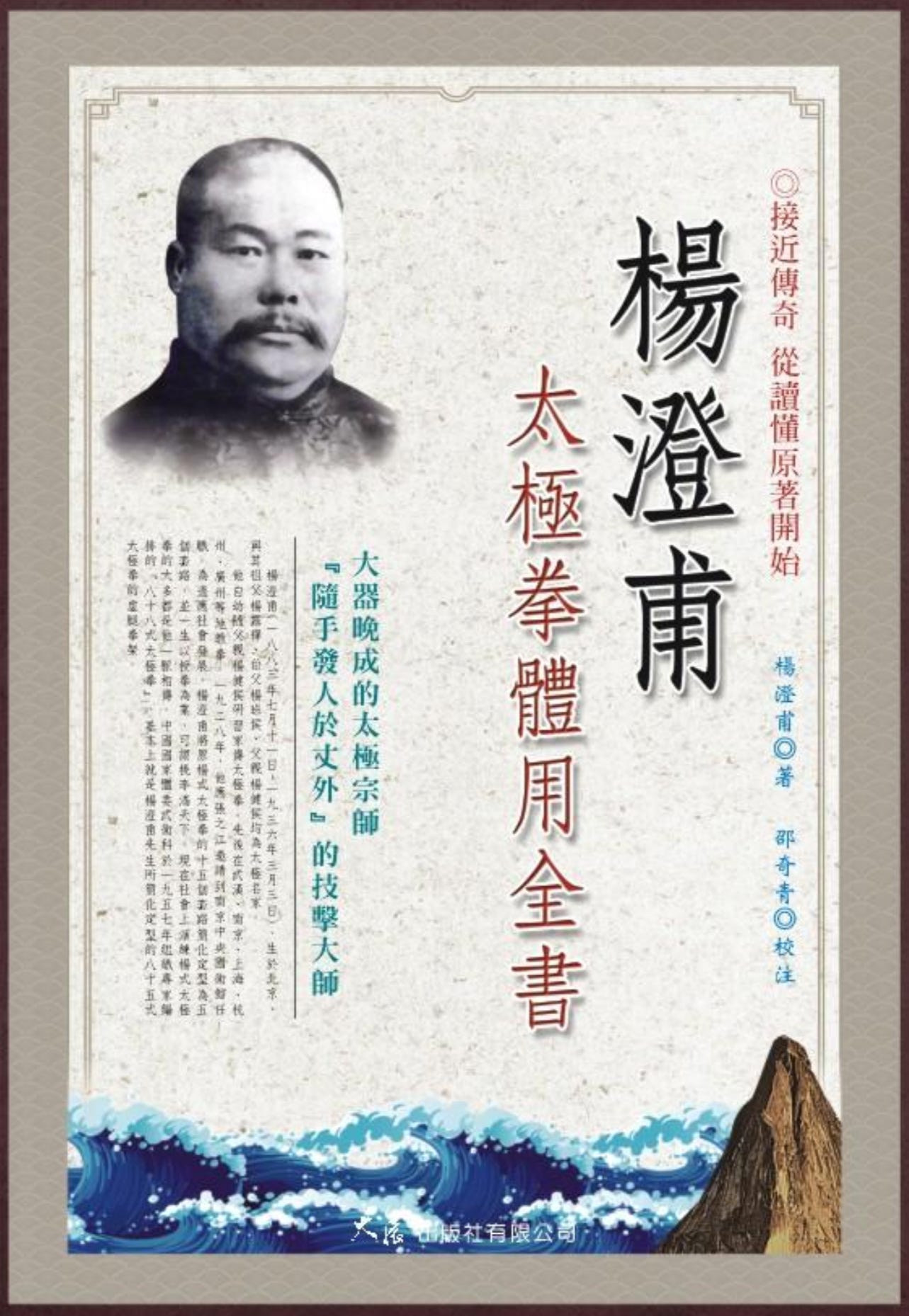

The Taijiquan Ten Essentials (Taijiquan Shiyao 太極拳十要) are studied by taijiquan practitioners around the world in order to apply the principles of the art to its routines and practices. Often called ‘The Ten Important Points,’ they first appear in print in later editions of Yang Chengfu’s (楊澄甫) second book, The Complete Book of Taijiquan Theory and Practice (Taijiquan Tiyong Quanshu 太極拳體用全書), coauthored with his student Zheng Manqing (Cheng Man-ch’ing 鄭曼⻘青).1

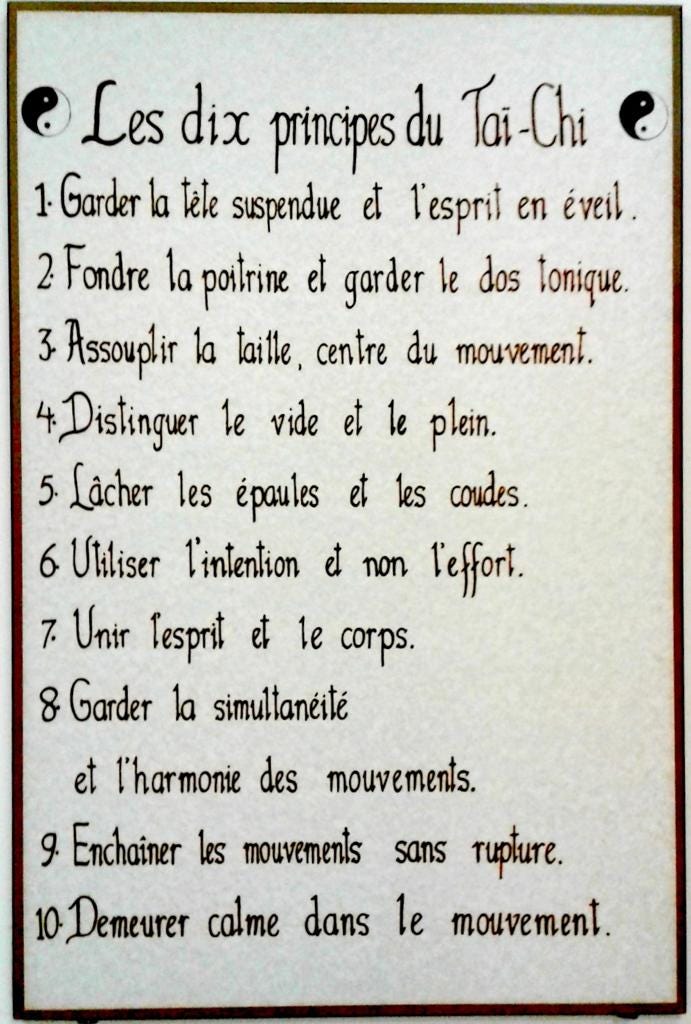

Taijiquan Ten Essentials (list) Taijiquan Shiyao 太極拳十要

1. Empty Neck, Raise Spirit xū lǐng dǐng jìn 虛領頂勁

2. Contain Chest, Raise Back hán xiōng bá bèi 含胸拔背

3. Loosen Waist sōng yāo 鬆腰

4. Differentiate Empty-Full fēn xū shí 分虛實

5. Sink Shoulders, Drop Elbows chén jiān zhuì zhǒu 沉肩墜肘

6. Use Intention, Not Exertion yòng yì bù yòng lì 用意不用力

7. Upper Lower, Mutually Follow shàng xià xiāng suí 上下相隨

8. Inner Outer, Mutually Harmonize nèi wài xiāng hé 內外相合

9. Connected Unceasingly xiāng lián bù duàn 相連不斷

10. Move Centre, Seek Calm dòng zhōng qiú jìng 動中求靜

1. Empty Neck, Raise Spirit (xū lǐng dǐng jìn 虛領頂勁)

Ding jin means: the head is maintained upright so the jin2 might pass though to the top. One must not exert, as exertion will stiffen the nape of the neck and the qi3 and blood will not circulate. One must be possessed of an open, spirited and natural intent. Without an open, spirited and natural intent, the jingshen4 cannot be raised.

一、 虛靈頂勁 頂勁者,頭容正直,神貫於頂也。不可用力,用力則項強,氣血不能流通,須有虛靈自然之意。非有虛靈頂勁,則精神不能提起也。

2. Contain Chest, Raise Back (hán xiōng bá bèi 含胸拔背)

Han xiong means: the chest is slightly restrained, enabling the qi to sink to the dantian.5 Avoid sticking the chest out: a protruding chest compels the qi surge into the torso. If one is top-heavy but light underneath, one’s footing is prone to instability.6 Ba bei means: qi adheres to the back. If one is able to contain the chest then one can raise the back. If one can raise the back, one can emit power from the spine and become unassailable.

二、 含胸拔背 含胸者,胸略內涵,使氣沉于丹田也。胸忌挺出,挺出則氣湧胸際,上重下輕,腳跟易於浮起。拔背者,氣貼於背也。能含胸則自能拔背,能拔背則能力由脊發,所向無敵也。

3. Loosen Waist (sōng yāo 鬆腰)

The yao7 governs the entire body. If one can loosen the waist, the feet will be powerful and the base stable. That empty and full transform, is entirely due to waist-turning; thus it is said, “Direct the will to the source at the waist-rift.” If one cannot achieve power, one must seek the defect in the waist and legs.

三、 鬆腰 腰為一身之主宰,能鬆腰然後兩足有力,下盤穩固。虛實變化皆由腰轉動,故曰:“命意源頭在腰隙”,有不得力必於腰腿求之也。

4. Differentiate Empty-Full (fēn xū shí 分虛實)

The art of taijiquan gives fen xu shi8 primary significance. If the body’s entire weight sits on the right leg, then the right leg is ‘full’ and the left leg is ‘empty’.9 Whole body weight sitting on the left leg means, the left leg is ‘full’ and the right leg is ‘empty’. If empty and full can be differentiated, turning can be light and quick and without wasted effort. Unable to differentiate, one’s footwork is heavy and stagnant, one’s stance is unstable and furthermore, one’s movement is easily influenced.

四、 分虛實 太極拳術以分虛實為第一義。如全身皆坐在右腿,則右腿為實,左腿為虛;全身坐在左腿,則左腿為實,右腿為虛。虛實能分,而後轉動輕靈,毫不費力。如不能分,則邁步重滯,自立不穩,而易為人所牽動。

5. Sink Shoulders, Drop Elbows (chén jiān zhuì zhǒu 沉肩墜肘)

Chen jian means: the shoulders are loose, open and allowed to hang down. If one cannot allow the two shoulders to let go, they will rise up; the qi will also follow upward and the whole body will be deprived of power. Zhui zhou means: the elbows drop loosely downward. If the elbows are strained upward, the shoulders cannot sink and an opponent cannot be sent very far. This is like the short, broken power of the external schools.

五、 沉肩墜肘 沉肩者,肩鬆開下垂也。若不能鬆垂,兩肩端起,則氣亦隨之而上,全身皆不得力矣。墜肘者,肘往下鬆墜之意。肘若懸起,則肩不能沉,放人不遠,近於外家之斷勁矣。

6. Use Intention, Not Exertion (yòng yì bù yòng lì 用意不用力)

In the Taijiquan Treatise10 it is written, “All movements are motivated by yi,11 not external form.” In training taijiquan the whole body must remain loose, avoiding even the slightest expression of crude force and the resulting stagnation which causes constriction of the sinews, bones and blood vessels. Consequently, one is capable of light, spirited transformations and can turn the circle smoothly.

Some question, “Without exerting power, how can one extend power?” The human body possesses the jingluo which can be likened to irrigation channels—if the irrigation channels are unblocked, water can flow through; likewise, if the jingluo12 are unobstructed, qi penetrates. If, from head-to-toe, the energy is stiff and the jingluo are blocked up, the qi and blood stagnate and body turning will not be nimble—when one place is tugged the whole body is pulled with it. If one does not exert, but rather uses intention, then when the yi arrives, the qi appears simultaneously. If the qi and blood flow fully—pervading and circulating daily throughout the entire body—there will be no stagnation. A long period of training this way will result in genuine internal power.

Another quote from the Taijiquan Treatise: “From extreme softness, comes extreme hardness.” Practitioners skilled in taijiquan gongfu13 possess arms that are like iron wrapped in silk—extremely substantial. Those training in external schools of martial arts exert themselves and the strength is obvious; but as a rule, when not straining, they float superficially. It is obvious strength, merely superficial and external in its expression. Not using yi but rather only li,14 it is easy to become agitated emotionally—this is not worthy of respect.

六、 用意不用力 太極拳論云:此全是用意不用力。練太極拳,全身鬆開,不使有分毫之拙勁,以留滯於筋骨血脈之間,以自縛束。然後能輕靈變化,圓轉自如。或疑不用力何以能長力?蓋人身之有經絡,如地之有溝洫。溝洫不塞而水行,經絡不閉則氣通。如渾身僵勁充滿經絡,氣血停滯,轉動不靈,牽一發而全身動矣。若不用力而用意,意之所至,氣即至焉。如是氣血流注,日日貫輸,周流全身,無時停滯。久久練習,則得真正內勁。即太極拳論所云:"極柔軟,然後極堅剛"也。太極拳功夫純熟之人,臂膊如綿裹鐵,分量極沉。練外家拳者,用力則顯有力,不用力時,則甚輕浮。可見其力,乃外勁浮面之勁也。不用意而用力,最易引動,不足尚也。

7. Upper Lower, Mutually Follow (shàng xià xiāng suí 上下相隨)

Shang xia xiang sui: The Taijiquan Treatise says, “The jin should be rooted in the feet, generated from the legs, controlled by the waist and expressed through the fingers. From the feet through to the legs and waist, the qi must always be integrated without any gaps.” Hand, waist and foot actions, and the expression in the eyes, likewise follow this movement. Following this principle can be described as: ‘Upper lower mutually follow.’ If one part does not move, instantly all is scattered and chaotic.

七、 上下相隨 上下相隨者,即太極拳論所云:“其根在腳,發於腿,主宰於腰,形於手指,由腳而腿而腰,總須完整一氣”也。手動,腰動,足動,眼神亦隨之動。如是方可謂之上下相隨。有一不動,即散亂也。

8. Inner Outer, Mutually Harmonize (nèi wài xiāng hé 內外相合)

Taijiquan trains the shen.15 Therefore it is said, “the shen is the commander and the body serves as a messenger.” If the shen can be raised, one’s actions will naturally be light and agile. The outer frame is nothing more than: ‘empty, full; open, close’. What is called ‘opening’ refers not only to the opening of hands and feet: the xin yi simultaneously opens. What is called ‘closing’ means, not only the hands and feet close: the xin yi16 simultaneously closes. To be able to harmonize inner and outer, thus unifying the qi, this must happen perfectly without gaps.

八、 內外相合 太極拳所練在神。故云:“神?主帥,身為驅使。”精神能提得起,自然舉動輕靈。架子不外虛實開合。所謂開者,不但手足開,心意與之俱開;所謂合者,不但手足合,心意亦與之俱合。能內外合為一氣,則渾然無間矣。

9. Connected Unceasingly (xiāng lián bù duàn 相連不斷)

In the external schools of martial arts, the power is ‘post natal’17 crude strength. Therefore, in starting there is stopping and continuity is interrupted. When the old strength is already exhausted and new strength has not yet been born—in this moment—it is most easy to be taken advantage of. Taijiquan uses ‘intention’ (yi) not ‘exertion’ (li); from start to finish, without end, it circles continuously without exhaustion. The original theory states: “Just as the Chang Jiang18 flows to the sea, it flows on and on unceasingly.”

九、 相連不斷 外家拳術,其勁乃後天之拙勁。故有起有止,有續有斷,舊力已盡,新力未生,此時最易為人所乘。太極拳用意不用力,自始至終,綿綿不斷,周而復始,迴圈無窮。原論所謂“如長江大海,滔滔不絕”,又曰:“運勁如抽絲”,皆言其貫串一氣也。

10. Move Centre, Seek Calm (dòng zhōng qiú jìng 動中求靜)

In the external schools of martial arts, jumping and flailing use up all the energy and power, inevitably leaving one gasping for breath after training. Taijiquan uses stillness to counteract movement and, while in motion, remains calm; therefore in training the form, the slower, the better. Slow, deep, steady breathing—qi sinking to dantian; one remains free of blood pressure diseases and hypertension. Students should ponder this teaching deeply to grasp its importance.

十、 動中求靜 外家拳術,以跳擲為能,用盡氣力,故練習之後,無不喘氣者。太極拳以靜禦動,雖動猶靜,故練架子愈慢愈好。慢則呼吸深長,氣沉丹田,自無血脈僨張之弊。學者細心體會,庶可得其意焉。

Footnotes

The first edition (1934) of Taijiquan Tiyong Quanshu included thirteen essential points but these were replaced with the ten set forth in subsequent editions of the work. The Taijiquan Shiyao were first taken down by Chen Weiming (陳微明) based on Yang Chengfu’s verbal transmission (kǒushù 口述). Verbal transmission was also passed to his eldest son Yang Shouzhong (楊守中). Yang’s first book, published in 1931, is entitled Taijiquan Practical Methods (Taijiquan Shiyong Fa 太極拳使用法).

jìn 勁 ‘spirit,’ energy’

qì (氣) ‘vital force’

jīngshén (精神) ‘spirit,’ ‘consciousness’

dāntián (丹田). Centre region and centre of gravity. Literally, ‘cinnabar field’, a reference to ancient daoist metaphysical practices.

fúqǐ (浮起) ‘floating’

yāo (腰) ‘waist’ and ‘small of the back’

xū-shí (虛實) also means ‘the actual situation,’ ‘theoretical versus practical,’ ‘false versus true’

This is a reference to the commonly used Chinese martial arts stance term xūbù (虛步) which means ‘empty step’

Note: the names Taijiquan Classic (Taijiquan Jing 太極拳經) and Taijiquan Treatise (Taijiquan Lun 太極拳論) have been used interchangeably to describe two different writings. What is referred to here as the Taijiquan Treatise is more often named the Taijiquan Classic.

yì (意) ‘will,’ ‘intention’

jīngluò (經絡) The meridian circulatory system in Chinese medicine.

gōngfu (功夫) ‘skillfulness acquired over time’

lì (力) ‘force,’ ‘strength.’ Refers to muscular power.

shén (神) ‘spirit,’ ‘essence’

xīn (心) ‘heart,’ ‘mind’ and yì (意) ‘will,’ ‘intent.’ Xīn and yì here refers to the complex of emotions and emotion-based thoughts (heart and mind) acted upon by the will.

hòutiān (後天) ‘post-heaven.’ Referring to the energetic conditions of the individual once born; and in contrast to xiāntiān (先天) ‘pre-heaven,’ the energetic conditions of life in the womb.