This piece, ‘The Upper Dantian,’ is Part Three of a description of the ‘three-centres’ (san dantian 三丹田) concept found in Chinese internal-arts practices for well over two millennia. The ‘upper dantian’ (shang dantian 上丹田), located in the head area, is often thought of as the ‘centre of consciousness’ and is related to the idea of ‘spirit’ (shen 精神), a term that can represent an aggregate of processes having to do mental activity and sense of self.

The upper dantian can be distinguished from the lower dantian (xia dantian 下丹田) and the middle dantian (zhong dantian 中丹田) not only by its location but also by the ephemeral processes it seems to rally. There are many ways that upper-dantian experiences are significant in a taijiquan player’s work—especially in terms of mastering the challenges posed by ‘conscious interiority’ and what is called ‘spiritual illumination’ (shen ming 神明).

Dantian possibilities

The term ‘dantian’ (丹田) describes the locus of a non-demarcated region or ‘field’ and represents the relationship between itself as a centre and what it is the centre of. For this reason it is usually referred to simply as ‘the centre.’ While the dantian can be described as an ‘infinite point with no magnitude,’ it is considered, nonetheless, to actually exist—even if in a ‘beyond-physical’ state.

A dantian possesses more than simple location—it is understood to ‘emanate,’ ‘resonate,’ and ‘discern.’ It is suggested that a dantian could, if properly understood and mastered, be used as a supra-sense organ—a tool for perception beyond that which people are normally accustomed to. In other words, a different level of insight awaits the individual who can achieve understanding of the internal world in this way.

… a different level of insight awaits the individual who can achieve understanding of the internal world in this way.

The upper dantian

The upper dantian (shang dantian 上丹田) is named and understood differently in various Daoist traditions. Some terms are used interchangeably to signify different locations and functions. Some upper-dantian related appelations include: the 'mysterious pass' (xuanguan 玄關), the ‘mysterious-pass one opening’ (xuanguan yiqiao 玄關一竅), the ‘empty pass’ (xuguan 虛 關), the 'heaven (or ‘creative’) chamber' (qiangong 乾宮), the 'heaven court chamber' (tiantinggong 天廷宮), and the 'hundred gatherings' (baihui 百會) which is also known simply as the ‘top opening’ (dingqiao 頂竅). Some of these designations, including the 'seal hall' (yintang 印堂), might be better understood as a false or ‘apparent dantian’ (xu dantian 虚丹田).

While these descriptive images differ from one another, they each point to an aspect of internal function or experience inside the head. A long and detailed exploration of internal processes and circumstances has led to a legacy that fuses description, belief, and metaphor.

‘Nine chambers’

In Daoist conceptions of the body, the centre of the head is imagined to contain nine ‘chambers’ or ‘palaces’ (jiugong 九宮). The three main chambers are: the ‘light-hall chamber' (mingtanggong 明堂宮), the ‘cavern-chamber palace’ (dongfanggong 洞房宮), and the ‘clay-pill chamber’ (niwangong 泥丸宮); the latter occupies the central position and is often used interchangeably with ‘dantian chamber’ (dantiangong 丹田宮).

From the surface of the forehead between the eyebrows, the mingtang is located inward by one inch (cun 寸, a cun being about a thumb width), the dongfang two inches, and the niwan-dantian at three inches. The ‘niwan,’ also called the ‘mud’ or ‘muddy’ pill, is the best candidate for upper dantian of those mentioned above.

This microcosmic inner view of the inside of the head was thought to resemble the structure of the macrocosmic night-time sky replete with zodiac-like deities. It is sometimes depicted as a stack of cubes (each approximately one cun in length) but also as an circular array of eight points with a centre (dantian) as the ninth. The nine chamber (or palace) idea has also been thought to relate to the eight bones of the cranium (frontal, two occipitals, parietal, two temporal, phenoid, ethmoid) and the centre in the midst of them.

Kunlun and Xiwangmu

Being located at the centre of the head, the upper dantian is sometimes referred to as ‘Kunlun’ (崑崙), a reference to the three-thousand kilometre long system of mountain ranges that stretch as far as parts of Tajikistan, Xinjiang, Tibet, the Tarim Basin, and the Taklamakan and Gobi deserts. The Kunlun mountain complex serves as a geological centre between China and the world to the west that, for the majority of the population living in eastern China, seemed a far-off place of mystery and wonder.

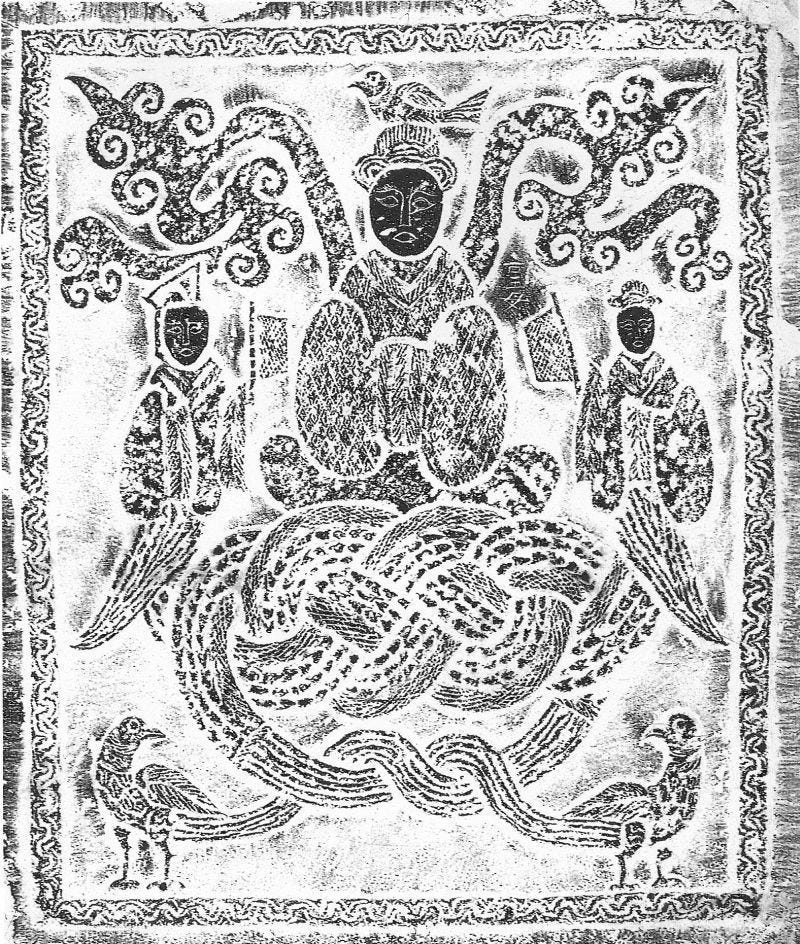

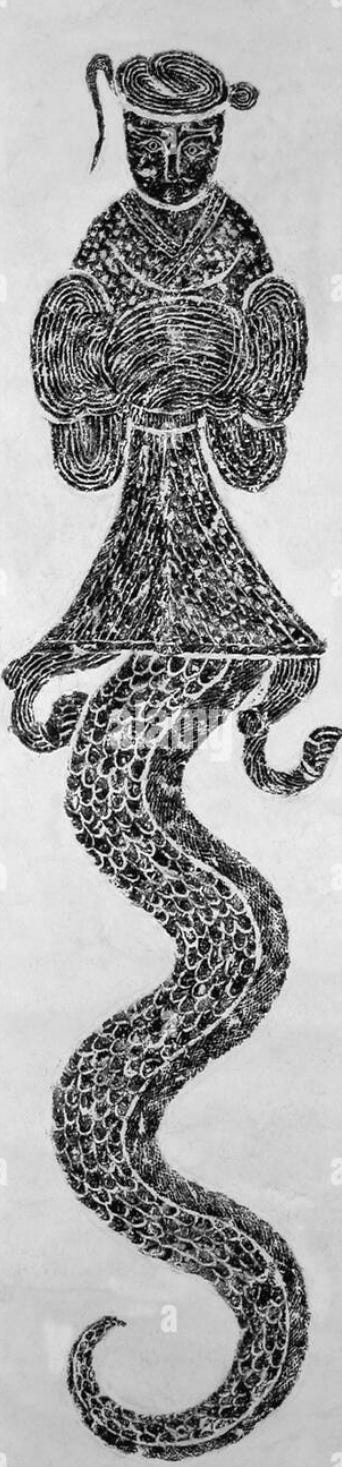

In legend, Kunlun Mountain (Kunlunshan 崑崙山) is a symbolic paradise and home to the much beloved immortal goddess 'Western Queen Mother' (Xiwangmu 西王母) who gives birth to yin and yang (yin yang’ (陰陽) in the form of the dragon/serpent-bodied couple Fu Xi (伏羲) and Nu Wa (女媧) a pre-human Adam and Eve. Xiwangmu, in her paradisal palace with its peach trees of longevity, can be seen as the dantian/locus of the ‘field’ that is Kunlunshan—an Eden-like centre of humankind and a meeting place for deities.

Kunlunshan and Xiwangmu can be understood as representing the place and the source of the emergence of the divided human brain—especially the so-called ‘reptilian complex’—represented by the scaly lail-like bodies of the sibling-lovers. Here, at the centre of the brain in the upper dantian/‘clay pill’ (niwan), is the 'mysterious pass' (xuanguan 玄關) between basic reptilian-mammalian functions and the conscious interiority that characterizes human cognition.

The brain

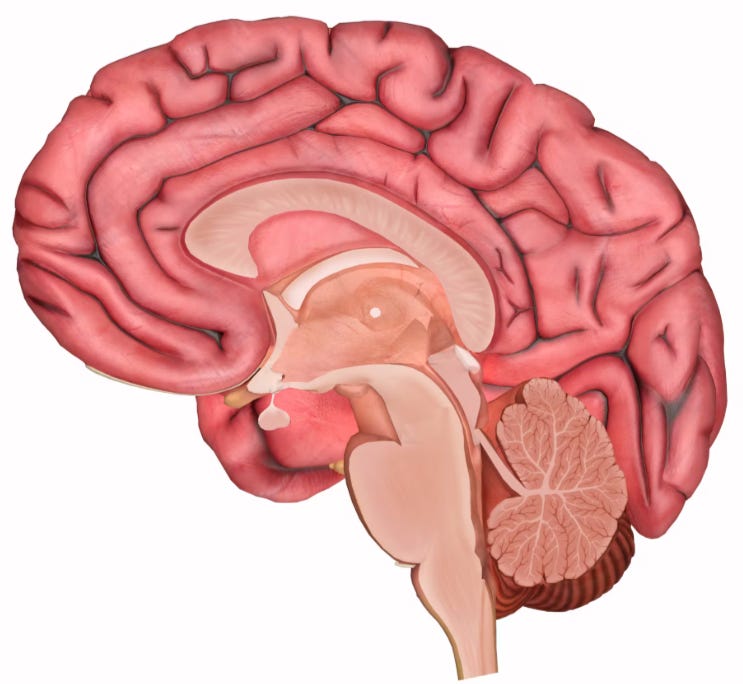

It would appear that the brain functions primarily in the service of metabolic efficiency and movement. However, with an organ so complex it easy to oversimplify its function, its ‘purpose,’ and its structure. For example, the persistent ‘triune brain’ concept—which is not used (formally) in contemporary neuroscience—postulates a simplistic way of thinking about the brain that accords, to a certain extent, with the traditional three dantians way of viewing things. This portrayal suggests that the brain is structured in three functional layers reflecting, what some consider to be, its own ‘evolutionary path.’ From this perspective the brain includes the: ‘premammalian complex’ (brainstem-cerebellum), the ‘paleomammalian complex’ (limbic system), and the ‘neomammalian complex’ (neocortex).

Regardless of the veracity of the triune brain concept it expresses the idea of a nested hierarchy of interrelated structures—something today’s neuroscientist is still driven to understand. Most functions of the brain are still not well understood and hypotheses abound. Here are some simple brain basics in a format that pertains to the dantian idea:

Brainstem and cerebellum

All nerve fibres connecting the brain with the rest of the body pass through the brainstem. It is, therefore, well situated to perform many basic regulatory functions such as: managing heart and breathing rates, adjusting body temperature (sweating and shivering), and adjusting hormone and blood glucose levels. The brainstem also plays a role in vision, hearing, and the fine muscular movements that generate facial expression.

Located at the back of the brainstem is the cerebellum, or ‘little brain,’ which is important in fine motor-skill activities and plays a major role in balance. A form of memory associated with the ‘physical-procedure recall’ of learned motor skills can persist in the cerebellum even when other memory faculties are damaged.

Thalamus and basal ganglia

The thalamus and basal ganglia are separate but interconnected parts of the brain.

The thalamus is, functionally speaking, the dantian of the brain. Sitting as it does at the top of the brain stem, the thalamus receives sensory and motor information that it then sends out to other parts of the brain. Alongside regulating motor function it is suspected that the thalamus is involved with memory and the integration of sensory input with cognitive functions.

The basal ganglia are comprised of several structures primarily understood as receiving information (particularly related to movement) from the cerebral cortex. It it thought to ‘processes’ and send select information to the thalamus which then returns to the cerebral cortex and the brainstem thereby activating the motor cortex in the frontal lobe. The basal ganglia are sometimes considered to part of the limbic system.

The limbic system

The limbic or ‘border’ structures within the brain are widely considered to be involved with emotion, learning, and memory processing. There is no single consensus on exactly which structures constitute this system, however, the main contenders are the hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus—others include the pituitary and pineal glands. The limbic system seems to affect interrelationships with similar or other kinds of creatures notably those involving arousal and sexual drive, fear and anxiety, as well as a wide range of emotional nuances.

The cerebral cortex

The outermost layer of the brain, the cerebral cortex is made of densely folded ‘grey matter.’ The folding allows for greatly increased neural activity in what is often called the ‘neocortex’ as it is considered to be a more recently evolved structure in vertebrates. Like most brain structures the cerebral cortex is divided into two symmetrical hemispheres. Joined together by the corpus callosum each side is broken into four basic regions that appear to act independently in some circumstances and in coordination with their counterparts in the other hemisphere in other situations.

The cerebral cortex is described as a six-layered structure with differences in cell type and density at each level. These brain structures function in many areas of sensing including somatosensory, auditory, visual, olfactory, and taste—the motor cortexes are also found here. It is widely held that the human capacity for abstract cognitive states such as the capacity to ‘experience in metaphoric space’ involves this part of the brain—but how the mechanism relates to such phenomenon is not at all understood.

It is interesting to consider compartmentalization of brain functions in light of the ancient concept of the nine distinct chambers described by early Daoist meditators.

The clay pill

The niwan (泥丸), is usually translated as ‘clay’ or ‘mud’ (ni 泥) ‘pill’ or ‘pellet’ (wan 丸). A wan is a kind of pill, a small clod of natural medicinal compounds wadded up into a ball-like pellet. The words wan (丸) and dan (丹) are visually similar and close in meaning (dan can also mean ‘pellet’) and it has been conjectured that the two may be divergent formulations of the same root character. The idea of wordplay here, where the dan of dantian and the wan of niwan are interchangeable, is compelling.

It is said that the ‘Great One’ (Taiyi 太一), a primal celestial concept and also a named deity, makes his abode in human beings at niwan but also in the cosmos at the ‘Northern Pole Star’ (Beijixing 北极星). Taiyi stands as the centre of human and cosmic fields and, according to legend, gave birth to ‘celestial water’ which is likened to ‘understanding.’

Niwan can be understood metaphorically through other mythical characters as well.

Nüwa

Myths describing gods fashioning creatures from clay is as universal as it is ancient. The Torah-Bible-Quran tell the story of the first human-being created from clay or dust and moulded into shape. Similarly, in a Chinese story of the origin of humankind dragon-bodied Nüwa moulded the first people from yellow clay. Nüwa had a human-like face and she fashioned the new creatures to resemble her own visage starting with the head. As the centre of the head is niwan, the starting point for what is ‘human’ about the human being—the yet-to-be-fashioned ‘clay pill’ or ‘muddy pellet’ from whence consciousness appears to appear.

Hundun

The term ‘hundun’ (渾沌) refers to a ‘primary and undifferentiated state’ and is also the name of a mythical character—Hundun—who exists-in and represents such a condition. Hundun is often translated as ‘primordial chaos’ and refers to a ‘muddy’ or ‘muddled’ condition—the ‘pre-taiji’ or ‘before-yin-and-yang’ state of reality better known as ‘no-polarities’ (wuji 無極). In the second foundational text of Daoism (Zhuangzi 莊子) the faceless Hundun comes to an odd demise when his colleagues Hu (忽) and Shu (儵) decide to reward him with human features by drilling seven holes into him.

Hundun can be understood to represent niwan, the muddy centre, where one possesses no features or personal characteristics—once one tries to imagine one’s unseeable face the primordial state is lost.

Shen

Where does the ‘outer’ or the ‘inner’ begin or end? From the standpoint of perceptual experience there is no satisfactory answer to this. In terms of what it is like where one is looking from there is no ‘head’ or ‘face’ to speak of—in this way one is like Hundun; headless. Paying attention to ‘what it’s like where one is looking from’ offers the possibility of a direct upper-dantian perspectival experience.

While the thalamus is a physical structure at the centre of the brain and the niwan provides an allegory for its behaviour, it is the ‘empty pass’ (xuguan 虛關) that stands between the world one perceives and the vantage point one occupies as he or she experiences that world. This is known as the 'mysterious pass' (xuanguan 玄關) which exists between what is experienced and who is having the experience. Here is found the location for the shen (神) experience.

The word shen has been translated many ways: ‘spirit,’ ‘deity,’ ‘essence,’ ‘soul,’ ‘expression,’ ‘mind,’ and more. Taking the most common definition, ‘spirit,’ as a starting point one is confronted immediately with a near insurmountable challenge in that this word can mean hundreds of different things in the English language. Often an individual has a strong connection with the word through their own personally applied meaning but to what extent this is understood by or shared with another person is wildly inconsistent. For example, the following are all meanings for the word ‘spirit.’

courage, energy, enthusiasm, essence, heart, humour, life, mood, morale, quality, resolve, temperament, vigor, vitality, warmth, will, air, animation, ardor, backbone, boldness, breath, dauntlessness, disposition, earnestness, eidolon, enterprise, fire, force, gameness, ghost, gist, grit, guts, liveliness, mettle, motivation, nerve, oomph, outlook, psyche, resolution, sparkle, spunk, stoutheartedness, substance, temper, tenor, willpower, zest feeling, genius, humour, meaning, purpose, quality, sense, tone, intent, intention, purport, substance, temper, tenor, timbre, apparition, phantasm, phantom, poltergeist, shade, shadow, spectre, spook, umbra, wraith, soul, supernatural being, vision—and there are many, many more.

Conscious interiority as ‘shen’

The lower dantian can be understood to focus the physical body, for example, as the centre of gravity or centre of movement. In terms of the brain’s structure this physicality is strongly related to the brainstem and cerebellum. The middle dantian is the centre of the viscerally-emotional area of human experience—the ‘heart realm’—connected strongly to the limbic system. The upper dantian—related as it is to the thalamus, which acts as a relay station for sensory and motor information—is, in internal-arts tradition, described as ‘the one that connects all three’ (yiguan santian 一貫三田). It acts not only as the link for the three regions but also is the centre of ‘conscious interiority.’

The capacity to introspect—to view and review ideated content in metaphoric space is a true wonder. On one hand, it is possible to think about memories, imagine scenarios, hear music, see images—even imagine oneself in this place or another. It is also possible to experience oneself as existing autonomously ‘within oneself’ and distinct from the ‘outside’ world.

This capacity for conscious interiority (shen) is thought to be a relatively recent development in human experience. In earlier periods of this development, inner voices and images were understood as directives and assistances of deities. Shen or ‘spirit,’ therefore, can be and most likely was, understood in this way—as an ‘altar at the centre’ for the ancestral.’

The twin and simultaneous processes of metaphoric and perspectival experience are in many ways fundamentally at odds with one another. The metaphoric experience exists almost entirely to generate and reconcile narrative structures. Perspectival experience, on the other hand, is direct and has no need or capacity for narrative. Quite naturally, this predicament results in a confused ‘muddiness’ at the ‘core’ (niwan the ‘muddy pellet’) that can only be clarified by means of observation and practice.

Oh, Primal Chaos! Ordinary folks are transparent—I alone am muddled.—Daodejing

If these apparent conflicts of process are not reconciled one potentially experiences ‘spiritual malaise’ (jingshen bushi 精神不适). Therefore, it becomes critical to engage in practices or activities that in some way reconcile the paradoxes and conflicts inherent in conscious interiority. It is in the upper dantian—the ‘mysterious-pass single opening’ (xuanguan yiqiao 玄關一竅)—that this work of clarification (ming 明) can, or even must, take place. As ‘the one that connects all three,’ the upper dantian is the place where intentional alignment can be begin.

In taijiquan the process of resolving the conundrums of conscious interiority involves a program of ‘self-cultivation through martial art.’ The successful result of this type of work is called ‘spiritual illumination’ (shen ming 神明) and requires one to learn to work with all three dantians during solo-movement activities and while engaging with partners. In the Taijiquan Treatise (Taijiquan Lun 太極拳論) this is described.

Gradually, as one’s touch matures (zhao shu 著熟), ‘comprehending energy’ (dong jin 懂勁) is awakened. As a result of ‘comprehending energy’ one progresses toward ‘spiritual illumination’ (shen ming 神明).

The exploration of the upper dantian in the practice of taijiquan provides one with a fascinating journey of self discovery that connects to universal and timeless questions about consciousness, existence, spirituality, and science.

Answers found in this journey may just be the clues to the next stages of human consciousness.

Enjoy this dialogue!

Writer, artist, and taijiquan instructor Caroline Ross in a fascinating interview with Iain McGilchrist discussing the brain, the mind, and life from the perspective of Ian's towering work ‘The Master and his Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World.’

Wow, that was a fascinating article Sam, brilliant explanation and research. One to read again a few times!